Do Smartphones Have a Place in the Classroom?

From middle schools to colleges, cellphones’ adverse effects on student achievement may outweigh their potential as a learning tool.

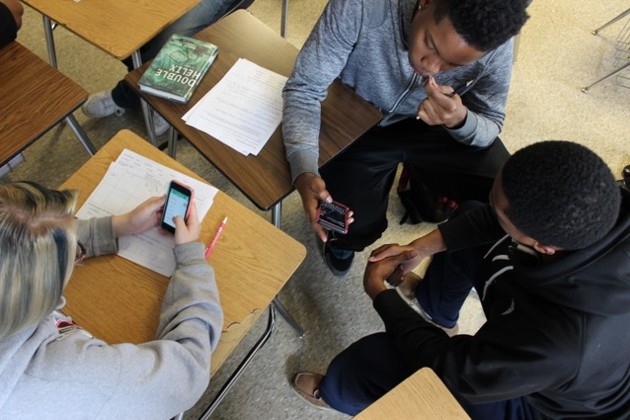

LOUISVILLE, Ky.—Walking the hallways between classes at Fern Creek High School in Louisville, Kentucky, I dodge students whose heads are turned down to glowing screens. Earbuds and brightly colored headphones are everywhere. And when I peer into classrooms, I see students tuning out their peers and teachers and focusing instead on YouTube and social media.

These are issues I deal with as an English teacher at Fern Creek. I have guidelines for cellphone and smartphone use, but it’s a constant struggle to keep kids engaged in lessons and off their phones. Even when I know I’ve created a well-structured and well-paced lesson plan, it seems as if no topic, debate, or activity will ever trump the allure of the phone.

Many teachers at Fern Creek are stumped about how to deal with student cellphone and smartphone use.

On the one hand, we know that most students bring a mini-supercomputer to school every day, a device with vast potential for learning. On the other hand, just how and even if smartphones might help students learn remains a troubling question. It’s especially vexing with regard to students who already have low achievement levels or learning problems.

According to our principal, roughly 75 percent of Fern Creek students are considered “gap” kids under Kentucky’s definition—students who belong to groups that, on average, have historically performed below achievement goals. These sometimes overlapping groups include students receiving free or reduced-priced lunch, African American students, English Language Learners, and special-education students. More than half of our gap students scored at the novice (lowest) level on last year’s 10th-grade reading exam. I frequently talk with colleagues about the possibility and challenge of using phones to help gap students from all backgrounds learn.

To us, it seems that some kids can handle the multitasking that using phones in school would require; for others, the smartphone is almost always a distraction. Even the visible presence of a phone pulls students—and many adults—away from their focus. Some kids can “switch” attention between the phone as an entertainment device and as a learning tool; for others, the phone’s academic potential is routinely ignored.

“The variance in student ability to focus and engage in the actual task at hand is disconcerting,” said Rob Redies, a Fern Creek chemistry teacher, via email. “Because although technology and the wealth of information that it can provide has the potential to shrink achievement gaps, I am actually seeing the opposite take place within my classroom.”

The phone could be a great equalizer, in terms of giving children from all sorts of socioeconomic backgrounds the same device, with the same advantages. But using phones for learning requires students to synthesize information and stay focused on a lesson or a discussion. For students with low literacy skills and the frequent urge to multitask on social media or entertainment, incorporating purposeful smartphone use into classroom activity can be especially challenging. The potential advantage of the tool often goes to waste.

And I know smartphones do have wonderful learning potential, having had occasional success with them in my own classroom. I’ve had students engage in peer-editing using cloud-based word processing on their phones, for example. I’ve also heard and read about other educators using phones for exciting applications: connecting students to content experts via social media, recording practice presentations, and creating “how-to” videos for science experiments.

We also know that other school districts across the country are in the midst of trying to incorporate technology to enhance learning, and to close the so-called digital divide—to ensure all students have access to an Internet-enabled device. One way to solve the access issue is to allow students to use smartphones in class. At Fern Creek, where I’d estimate that at least 80 percent of students have smartphones, this would seem like a logical choice, given the relatively low numbers of tablets and computers we have available for student use.

Because of my own frustration with school phone use, and spurred on by conversations with colleagues, I decided to delve into the research about smartphones and education. Can and should smartphones be used to enhance learning for all students? Or should we avoid using phones in class because of the distractibility factor, and because many kids seem resistant to using them for learning?

Research supporting the idea that smartphones—specifically—can be used to enhance learning for all students, even underachievers, is hard to find. However, Stanford University’s 2014 study on at-risk students’ learning with technology concludes that providing “one-to-one access” to devices in school (students don’t have to share) provides the most benefit. The study does not, however, mention smartphones as a choice tool to achieve greater engagement and academic success.

I next contacted Richard Freed, a clinical psychologist and the author of Wired Child: Reclaiming Childhood in a Digital Age, who works with a wide range of children and families in the San Francisco Bay area.

“High levels of smartphone use by teens often have a detrimental effect on achievement, because teen phone use is dominated by entertainment, not learning, applications,” he said.

I considered the Stanford study and my conversation with Freed as I observed students in my own classroom. Struggling students (from all backgrounds) seem to be more susceptible than their higher-achieving peers to using their smartphones for noneducational purposes while in school. Also, the device does make a difference: When I design and schedule instruction allowing for one-to-one computer access, students get better results than when I try the same thing with one-to-one phone access.

Nonetheless, Redies and I and many of our colleagues attempt to use smartphones productively in class, but I don’t know of any Fern Creek teacher who allows students open access to their devices at all times. This contrasts with the approach of Brianna Crowley, a colleague with whom I’ve worked through the Center for Teaching Quality.

Pennsylvania’s Hershey High School, where Crowley taught English for eight and a half years before recently leaving the classroom for a full-time consulting job with the Center for Teaching Quality, is part of a high-achieving district with few disadvantaged students. For three years, the district has been implementing a “bring your own device” (BYOD) policy in an effort to maximize students’ learning opportunities.

Still, even Crowley has noticed the challenges for struggling students. “Many students who may perform poorly on academic measures seem to see their devices as useful for a narrow range of tasks—most of which involve passive consuming of entertainment or knowledge-level content,” she wrote in an email. If all students are to be successful using smartphones and other technology for learning, Crowley added, then it’s clear that different students may need different activities and different types of support from teachers.

But at schools like Fern Creek, the fact that so many students have below grade-level reading skills, coupled with their tendency to use their phones for entertainment in school, means that teachers here are having a tougher time figuring out how smartphones might support learning.

Fern Creek’s principal, Nathan Meyer, recently asked faculty members to provide input on how to best address the challenges of integrating (or not) students’ smartphones into the learning environment. “I see students using cellphones and earbuds as a way to disengage with their peers,” he said. “The isolation squanders opportunities for students to learn to engage and communicate with empathy.” The cellphones and easy access to social media, according to Meyer, are also at the root of much of the student disruption and conflict that happens on campus.

The findings of a recent study on student phone access and the achievement gap by Louis-Philippe Beland and Richard Murphy for the London School of Economics and Political Science echoed my concerns. “We find that mobile phone bans have very different effects on different types of students,” the authors wrote. “Banning mobile phones improves outcomes for the low-achieving students … the most, and has no significant impact on high achievers.”

The study focused on standardized-test data, however, and many educators, like Crowley, question the usefulness of that measure; they would prefer to evaluate learning based on more varied, deeper measures, such as student projects.

“We shouldn’t put these results on a pedestal,” Crowley said.

Yet analyses of other academic metrics seem to support limiting students’ smartphone access, too. Researchers at Kent State University, for example, found that among college students, more daily cellphone use (including smartphones) correlated with lower overall GPAs. The research team surveyed more than 500 students, controlling for demographics and high-school GPA, among other factors. If college students are affected by excessive phone use, then surely younger students with too much access to their phones and too little self-control and guidance would be just as affected academically if not more.

Some school districts with large percentages of struggling students have forged ahead to increase student access to their phones. Last year, New York City’s public-school system lifted its ban.

“It’s like giving kids equal access to cigarettes and candy,” Freed said. “There is a reason that adults have tried to limit and regulate young people’s behavior, given that teens are not as adept at understanding risk and cause and effect.”

However, Crowley believes teachers must adapt classroom instruction to the modern world. “If educators do not find ways to leverage mobile technology in all learning environments, for all students, then we are failing our kids by not adequately preparing them to make the connection between their world outside of school and their world inside school,” she said.

So, is the best learning environment one that’s free from digital distractions for struggling learners—a refuge from the constant barrage of information? Or should schools adapt to the realities of a hyper-connected world in which the vast majority of students carry access to almost-infinite information in their pockets? Or is there a middle ground?

For myself, Redies, Meyer and the staff at Fern Creek—and at many other schools serving large numbers of disadvantaged learners—there is no simple answer.

This post appears courtesy of The Hechinger Report.