Emerging Technologies as a Cause of Shadow Work

In “Shadow Work: The Unpaid, Unseen Jobs That Fill Your Day,” Craig Lambert argues that the upsurge in unpaid tasks (shadow work) that we do on a daily basis increasingly erodes our free time while eliminating jobs and reducing the cost of products & services. Today, it is we who fill the tanks of our cars, bag our groceries, make travel reservations, drive our kids to school, and manage most personal banking operations and a myriad of other activities. Thirty years ago, paid professionals did it.

In many instances, we prefer and choose to do shadow work: by making our own vacation arrangements, we feel that we arrive at the best equilibrium between the value we get and the budgets we can afford; by using software to do our own taxes, we increase our chance to file them correctly at a lower cost than that afforded by a tax professional. We pay a price in terms of time, but we feel that that price is justified by the value we get in return. However, in other instances, doing shadow work is neither a preference nor a choice; taking, for example, additional responsibilities for the same compensation after a company goes through a downsizing amounts, in most instances, to doing unpaid work.

In addition to the democratization of expertise, the information dragnet, and constantly evolving social norms, Lambert identifies technology and robotics as one of the four major forces that explains the upsurge in shadow work. But in my reading, Lambert seems to primarily emphasize the role that mature technologies have in enhancing the amount of shadow work we do. What I would like to argue here is that emerging technologies are a more perfidious cause of shadow work.

Let’s discuss two emerging technologies in more detail, in the context of two services: Speech Understanding in customer call support centers and Machine Translation in language translation services. During the last decade, both technologies have improved in leaps and bounds. As a consequence, they are incorporated more and more aggressively into larger solutions.

Nowadays, when we call a vendor to ask for support, we are most likely greeted by a machine that is not smart enough to replace a customer support agent and understand what we are saying, but smart enough to take us through a pre-programmed sequence of choices and sub-choices in an effort to fit our question into a category for which the answer can be provided automatically. The machine cannot understand reliably a question such as “what is the balance on my credit card?” so it takes us through a long list of questions: “if you are calling about your bank account, press 1; if you are calling about your grandmother, press 2; …; if you are calling about your credit card, press 9;” Once we press 9, we get other questions “if your credit card is blue, press 1”, and so on. After we pressed keys or spoke digits for 5 minutes, we may get the answer we are after; be sent back to the original menu to start from scratch because we might have missed saying the right number at the right time; or offered the chance to speak to an operator. The five or ten minutes that we spend on the phone interacting with a call center software system is emerging technology caused shadow work. We do that work because automatic speech understanding technology is not good enough to figure out as quickly and reliably as a human what we actually need.

Doing 5-10 minutes of emerging technology-enabled shadow work every time we make a call is annoying. But doing shadow work every day, as part of our regular job, is more than annoying; it is unfair. Let’s examine the shadow work professional translators do when working on post-editing jobs.

Three decades ago, translation work was easy to compensate fairly. When an organization wanted to translate a document, it counted the number of words in the document, negotiated a translation price with a professional translator and paid for the translation service when the translated document was delivered. Two decades ago, things got a bit more complex. As enterprises started storing their translations into large databases, called translation memories, they were able to identify whether sentences in a document to be translated were translated before. That technology is still used today.

When, let’s say, Fitbit Charge HR was released in January 2015, the product documentation that came with it had many sentences that were part of the Fitbit Charge product documentation, which was released in November 2014. In preparing for the Fitbit Charge HR release, source sentences that matched 100% sentences that were translated before could be simply retrieved from the translation memory and the translator could be paid only to review the extent to which a translation produced several months back would still fit into the context of the new documentation. And source sentences that had a very high, but not perfect, match with sentences that were already stored in the translation memory could be also translated at a discounted price since the amount of work was lower. If Fitbit had, for example, a Spanish translation for the sentence “Radio transceiver: Bluetooth low energy”, which came with the Fitbit Charge documentation, it would have been reasonable to pay less for translating “Radio transceiver: Bluetooth 4.0”, which came with the Fitbit Charge HR documentation. A professional translator would have needed only to replace the translation of “low energy” with “4.0” in order to obtain a perfect translation.

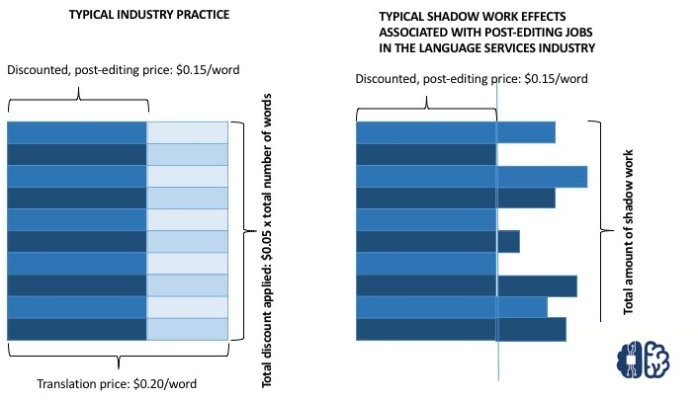

As Machine Translation has improved, localization departments and language service providers have started to use it more and more as part of their internal processes. Today, they typically pre-translate a document with an automatic translation engine and ask their translators to post-edit the outputs at a discount. Instead of being paid a full price, professional translators are paid the discounted price for each word in each sentence they translate (see the left side of the leading Figure). The problem is that this type of pricing is not in sync with the reality because Machine Translation systems cannot provide, by design, consistent quality. For some sentences, they produce very good translations, for which applying a discount is justified. But for many sentences, they produce low quality translations that cannot support increases in translation productivity and for which applying a discount is not justified. Today, all deficiencies associated with the adoption of an emerging technology – machine translation – are absorbed by professional translators: they end up doing unpaid, emerging technology caused shadow work (see the right side of the leading Figure for a graphical illustration).

Doing 5-10 minutes of shadow work whenever we call a customer support center is not the end of the world. Some of the customer support cost reductions that are enabled by we cooperating with an emerging technology could, most likely, be passed on to consumers via reduced prices. However, doing daily unpaid shadow work to accommodate an emerging technology is a completely different matter. Nobody could feel right when they spend 15-20% of their workday doing un-compensated work.

I am in the process of compiling a list of cases in which the adoption of an emerging technology creates shadow work. If you want to share such cases from your own industry, please comment on this post or email me directly; your insights are appreciated.

Rethink Your Child's Education with Wilson Hill Academy

8yI think part of the "Shadow Work" problem with MT that you use as your example can also be attributed to the macro business model for translation. 1. The MT vendor makes claims about productivity gains in an effort to sell the the technology to the LSP. 2. The LSP, needing to generate ROI in the MT investment, expects a discounted rate from the translator based in assumptions about productivity gain ... often vendor-supplied assumptions that the LSP is not really qualified to validate. 3. The translator is left with the choice of accepting the lower rate (and the accompanying "shadow work") or declining (possibly giving up future opportunities with that LSP as a result). It seems to me that a word rate approach that once made sense, and that automatically allowed better/faster translators to earn more without the buyer having to understand the process, no longer fit the technology-enabled environment we are now in. Rather than continuing to force everything into some sort of "corrected" word rate model, the industry really needs to put its big-boy pants on and figure out how to identify and compensate better/faster translators while simultaneously investing in technologies that can improve productivity across the board.

Translator DE/IT/EN/SE-DA

8yHi Daniel, thank for casting a little light over some of these aspects. I was wondering why you do not mention crowdsource translation. There are many noble crowsourced translation projects (Ubundu, just to mention one) where most, if not all, benefits go to the users. However, when it comes to healthy for-profit companies using unpaid crowdsourcing to translate their content, wrapping the whole operation up in candy floss marketing language like: ‘our community is made up by experts, they are minds, highly valuated, who would be better to …, an alarm bell should trigger. Recently the billion $ toy company LEGO Group, in collaboration with their LSP, launched crowsourced translation. The following is an extract from an interview explaining the business model in a nutshell. (The whole interview can be found here: http://www.collaborative-economy.com/project-updates/crowdsourcing-week-europe-lessons-learned/) LSP: “We had a client, LEGO … so what we did was, instead of doing traditional translation, which would have been simply finding a professional translator to do the work, we decided to tap into LEGO’s own rich community of adult fans. So, what we did was, we ended up recruiting, and testing of course, they are wedded for their linguistic ability, 20 people to then help us translate from English to German. What we found is that we were able to translate 60,000 words in three and a half days, and these people all work full time. Q: “And they were all LEGO fans?” LSP: “They were all LEGO fans; they work for free, right. And they wanted to. We found the biggest problem, when we had finished with the project. Thursday afternoon, when we had finished, the biggest problem was, there wasn’t more to translate. We had a lot of emails (…) saying were is more text? We want to translate; we want to be more involved. So that was actually our biggest problem.” The LEGO group is one the world’s most profitable toy making companies in the whole world, with record-breaking profit growth. What would the cost of 60,000 words have been? Ridiculous! Put on high a scale, can you imagine the number of words that hundreds of enthusiastic community members will be able to produce? Up until today, I also thought that experts were something you pay for, rather expensively. Should we conclude that a conversely Robin Hood trend has been set for the future in the translation industry, and that LSP’s and billion dollars profit companies now move from regularly paid work to unpaid full time work? That’s what people want, no? After all, they volunteer. Win-win means money to me and involvement and likes to you. Is this a new business model for the future? Perhaps it is time to talk about Large Scale Human Translation and Crowdsourcing as a competitor to MT in terms of investments and profits? The only reason I can think of why not to deal with this subject here, is that you are planning to write a separate post about unpaid work in full daylight.

Gravure Cylinder Engraving for the Packaging Industry

8yGreat thoughts there. It's never good to unfairly take advantage of translators.