From craft brewing to farming, more and more entrepreneurs are choosing to stop competing with their rivals and work with them instead. Whether it is a one-off project or a longer term arrangement, these collaborations can pay off, with both sides gaining new customers and saving cash.

We speak to small business owners making it work.

‘We let the creative juices of the two brewers mingle’

The craft beer industry has seen tremendous growth in the past five years. In July 2015, the British Beer and Pub Association reported that there were now 1,431 breweries in the UK.

But despite all these businesses jostling for market share, there is a surprising amount of collaboration between them, says Gregg Irwin, co-owner of Weird Beard Brew Co in Hanwell, west London. He says it’s about ensuring the longevity of the industry for everyone: “We are making the same product and theoretically fighting for space – in bottle shops, in the pubs. But we’re working together to make the beer sector grow.

“If we work together and make a big thing out of craft beer, hopefully more people will ask for it, more pubs will stock it, more pubs will open to keep up with the demand.”

Weird Beard was founded by Irwin and co-owner and head brewer Bryan Spooner three years ago. Irwin estimates it has already done 25 collaboration brews. Some are repeat offenders. The company has worked with Northern Monk Brew Co in Leeds three times, producing Bad Habit, Blue Habit and Becoming a Habit together. On the day we spoke, the brewers were bottling a beer they had made with New Zealand brewers 8 Wired.

The joint brew is often first discussed over a pint at a beer festival or brewers event. Irwin says the brewers Weird Beard works with tend to be friends, or a brewery they really respect.

A collaboration brew can take many forms, but typically the two brewers will discuss a recipe, bouncing around ideas for a malt or hop they want to use, before coming together for the actual brew. The packaging and distribution costs are managed by the “host” brewery and both companies have their name on the bottle.

“There’s not really a saving in costs,” Irwin says. “But the main benefit is sharing of knowledge. Every time you brew with someone new (whether it’s at your brewery or theirs), you learn something.

“Exposure is another advantage. If you collaborate with a bigger brewery and they have a substantial distribution network, they’re going to be sending something out with your name on it. We’ve gotten into new markets that way – sales in Sweden, Norway and France have all come from collaborations.”

Irwin says so far they have never fallen out with another brewery on the back of a collaboration brew. “We just let the creative juices of the two brewers mingle and let it go. Generally something interesting will happen. It’s fun – that’s the point.”

‘It’s opened us both up to new audiences’

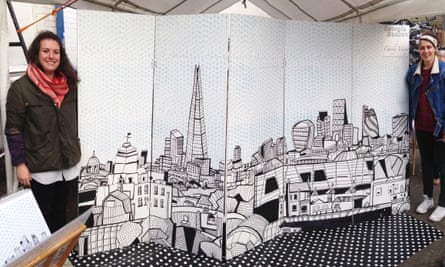

Artists Georgia Bosson and Cecily Vessey have also found that working together has increased their individual networks substantially.

They met through the Crafty Fox Market in London, when Vessey was appointed as newcomer Bosson’s mentor. “I hadn’t had a stall before so sent a lot of questions by email about where to park the car, how much stock to bring, what float to have …” Bosson laughs. “Her advice made me feel more secure about the whole thing.”

A number of popup shows followed, but it wasn’t until they were both running a stall at the We Make London gallery that they worked collaboratively together, when the manager suggested they draw on a wall that wasn’t being used. “In the space of a week, we would just sketch when the shop was quiet,” Vessey says. “It was a really nice way to talk about our work, so we decided to do a bit more together.”

Their styles are very different – Bosson is a screen-print artist who works with a lot of textiles and Vessey draws cityscapes that are reproduced on to ceramics and stationery. But, Vessey says, their two techniques “have come together in a really lovely way”.

They are now working on a series of 12 prints, which they are hoping will be ready by October. There have been other popup gallery shows as well, and both women list their collaborative work on their own websites. The benefits have been extensive. They can share the costs and tasks involved with running a show, have found new customers through each other, and each offers a sympathetic ear when it comes to discussing the challenges of running a small creative business.

“It’s a much more enjoyable way of doing this kind of thing,” Vessey says. “We meet for lunch every couple of weeks and you come away feeling a bit clearer, even if it’s about your own work rather than the collaborative project.”

Bosson agrees: “It’s also opened us both up to new audiences. My customers are incredibly different, but the response has been great, people really like it.”

Their advice to making it work? “It has to feel instinctive,” says Bosson. “This happened accidentally so we’re relaxed about it.” And neither woman puts all of her eggs in this collaborative basket. “It’s a side channel of our businesses. It’s one that really helps with everything, but if this fails, our businesses won’t fail,” Vessey says.

‘We had an easy exit if it didn’t work out’

Rob Addicott and Jeremy Padfield have been collaborating for 16 years. Their neighbouring family farms in Somerset – Manor Farm and Church Farm – share machinery and an employee.

“We both had traditional mixed farms in the late 1990s, but within a year of each other, sold our daily herds and decided to focus on growing our crop businesses,” Addicott says.

“The machinery is really expensive so we said, why don’t we put our toe in the water and share.”

Beyond the machinery, Addicott and Padfield have also collaborated to explore new business opportunities, helping each other out when it would have been easy to compete instead. When an option came up to buy some more nearby land, they submitted a bid together and split it between the two farms when they were successful. They’re also building a contracting business together, using their new machinery to work on other nearby land.

“There are aspects of the business we don’t share,” Addicott says, citing Padfield’s equine operation and his office-leasing business. “But since we started collaborating, we have found that our skill sets work well together. I’m technology driven, Jeremy is more focused on marketing. We knew each other relatively well before so haven’t had to formalise things too much. We started quite small and had an easy exit if it didn’t work out.”

Padfield agrees: “There are cost savings and we’ve been able to invest in more precision farming equipment much earlier than would have been possible otherwise. We’re trying out niche crops such as canary seed at the moment. It’s a risky crop but with both of us growing it, that risk is spread.”

The pair have explored collaboration with other networks too. The agriculture and horticulture development board’s cereals and oilseed chapter has organised an initiative called Monitor Farms to encourage discussion and knowledge sharing among its members.

“If you’re with a group of people willing to write down what they’re spending, it benefits everyone,” says Addicott.

He is also a member of Crop Advisors, which provides economies of scale privileges on seeds, fertiliser and agrochemicals, to smaller farms.

“People have realised that farming is a lonely job. The industry’s changed very quickly,” Addicott says. “I think collaboration is the future of farming for smaller scale farmers.”

Sign up to become a member of the Guardian Small Business Network here for more advice, insight and best practice direct to your inbox.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion