Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud drives an old, navy, four-door Mercedes C220, which was easy to spot among the Renaults and the Opels massed in traffic at the RER station on a rainy Wednesday rush hour. We shook hands when I got in, and he warned me not to slam the door. In an attempt to pry the passenger side mirror off years ago, a would-be thief had damaged the housing, which a series of mechanics had never managed to re-attach more lastingly than with masking tape.

Châteaureynaud had just come from signing 300 press copies of his latest book, a memoir of his early life from Grasset, entitled La vie nous regarde passer [Life Watches Us Go By].

“I lost fifteen copies,†he said. “I left them in the metro. The stockroom did a good job sealing the box up really tight, so instead of trying to open it, the police have probably blown it up by now.â€

“It’s one way to spread the word… or words,†I said.

“Yes… you could say that book really burst onto the scene!â€

Châteaureynaud’s latest work of fiction, Résidence dernière [Final Residence], had come out a few weeks earlier from Les Éditions des Busclats, a small press founded by poet René Char’s daughter, Marie-Claude, and her partner, critic Michèle Gazier. Since 2007’s De l’autre côté d’Alice [Through a Looking Glass Darkly]—three adult meditations on popular children’s heroes Alice, Peter Pan, and Pinocchio—Châteaureynaud had been experimenting with thematically linked triptychs of short stories. The tales in Résidence dernière, featuring a decrepit sphinx, a magic mirror, and a nightmarish limbo, revolve around writer’s retreats, examining such typically Castelreynaldian themes as solitude, the anxiety of creation, and the writing life. I thought the final, title story among the finest he’d written. In it, a number of aging writers, worrying over posterity, find themselves on a bus headed for a mysterious residency.

“The bus is in homage to a remarkable book by C.S. Lewis, L’Autobus du paradis—have you read it?†I later realized I had, when I found out the English title: The Great Divorce.

Châteaureynaud lives, fittingly for a fabulist, on the rue Jules Verne in a neighborhood of houses that date mostly from the 1930s. The blocks, delimited by less than rectilinear streets, are divided into oddly-shaped lots; his own yard, menaced by vegetation dense with bird twitter, seems cramped from the porch but surprisingly large once you’re in it.

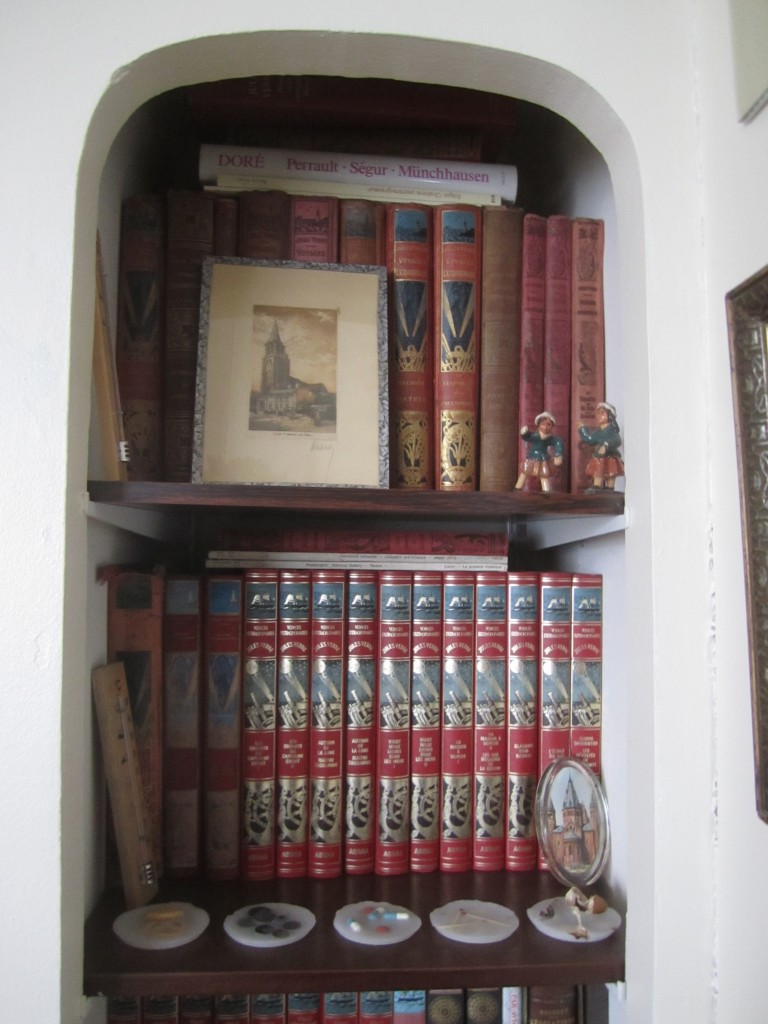

An alcove off the dining room is stocked top to bottom with the handsome red “Hetzel Collection” Hachette hardcovers of Jules Verne, a few postcards and figurines propped against the gilt backdrop of their spines.

In a corner of the glass-fronted armoire, among china services collected from his days as an antiques dealer, the certificate naming Châteaureynaud a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur stands rolled up in its original mailing tube. A photocopied picture was wedged between mirror and frame, above the liquor cabinet.

“Guess who it is?†G.-O. asked. A weathered-looking Vonnegut with a hat and a cane stared out from a street corner. “He does look like me, doesn’t he?â€

From half a hollow Greek column rose a plastic tree with wrinkly fabric leaves. It was hung, like the chandelier, with glass Christmas ball ornaments of faded tint and a few tarnished silver acorns, lending the room the forlorn charm of unforgotten holidays. On the wall opposite were a few framed photos of roses from the garden, and a reproduction of “The Iron Age†by Belgian Surrealist Paul Delvaux, one of Châteaureynaud’s favorite painters. Delvaux’s “The Blue Sofa†(also J.G. Ballard’s favorite painting) plays a part in Châteaureynaud’s novel Mathieu Chain, and appears on the cover of the first paperback edition.

“The faces of his nudes sometimes remind me of Balthus,†I remarked.

“Yes, but Balthus has a pervert’s gaze,†he said. “Delvaux’s women are always innocents.â€

G.-O.’s younger son Mathieu, a union organizer and dungeon master, popped in to say he would not be dining with us. He was on his way out to see True Grit. G.-O.’s older son, Georges-Thomas, was a guitarist who’d played a few gigs in the U.S. last month. He had recently rechristened his band Tchad Solero, and released a video.

“Have you always encouraged your sons to follow their artistic impulses?†I asked.

“At first, definitely. Then at a certain point they start worrying about a career and a stable income, and you do too. I’ve had so many odd jobs my pension’s a mess; so be it. But you want a better life for your children.â€

G.-O. was breaking ice from a tray into glasses he’d filled with a punch of his own concoction: dark rum, whiskey, and freshly squeezed orange juice. We were discussing the French fabulist Noël Devaulx, whom we both admired: his enigmatic stories, and his personal reticence. I’d recently read the final interview Devaulx had given, to Châteaureynaud’s friend and fellow writer Hubert Haddad, in which his responses had been almost willfully unilluminating.

G.-O. said that he himself had met Borges’ friend, the Argentine fabulist Adolfo Bioy Casares, “in Nice once, or maybe Cannes. Somewhere warm.â€

He’d asked Bioy Casares a question only to be met with practiced deflection. “But he was very old by then, you know; I don’t think he could’ve stood up straight without his nurses, who were very pretty.â€

I pictured the author of The Invention of Morel, one of Châteaureynaud’s favorite novels, flanked by a pair of Russ Meyer valkyries. Among the many ways in which meeting Georges-Olivier has not disappointed me is that he never plays the persona card. You have the feeling of talking to a real person who pays you the compliment of his attention and does his best to answer, an approachability almost shocking in a public figure. There is, of course, the hat and the merry air of slight befuddlement most often worn at book fairs, but even that, one suspects, is less pretense than actuality, and endearingly human.

[to be continued…]

Leave a Reply