OTL: Deadly Games

IO DE JANEIRO -- A white cross rising above the Macacos slum marks the spot where people are burned alive. A starving horse, his ribs poking out, is hitched close by with a thin rope. A nearby soccer field is dotted with pieces of melted rubber. No games are played here. The Amigos dos Amigos gang that runs this favela has a ritual: Members stack tires around their enemies, pour in gasoline and light the tires on fire. This is called microwaving. Black smoke rises into the air. At a school down the hill, near the famous soccer stadium where the 2016 Olympic opening ceremonies will be held, the students hear the screams and cover their ears.

IO DE JANEIRO -- A white cross rising above the Macacos slum marks the spot where people are burned alive. A starving horse, his ribs poking out, is hitched close by with a thin rope. A nearby soccer field is dotted with pieces of melted rubber. No games are played here. The Amigos dos Amigos gang that runs this favela has a ritual: Members stack tires around their enemies, pour in gasoline and light the tires on fire. This is called microwaving. Black smoke rises into the air. At a school down the hill, near the famous soccer stadium where the 2016 Olympic opening ceremonies will be held, the students hear the screams and cover their ears.

This is Rio in real life.

Wishful thinking in living color

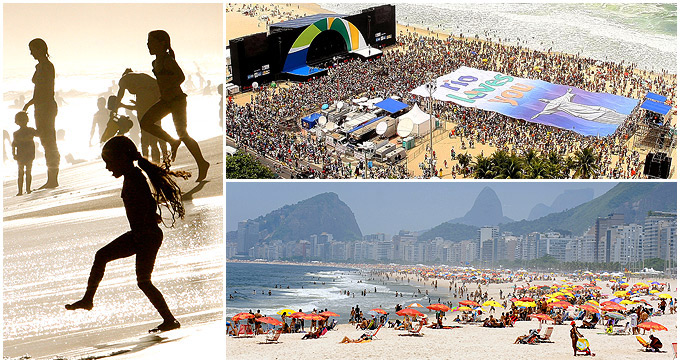

This is Rio in the imagination of the 2016 Olympic planners: a 19-page brochure full of color photographs and grand statements outlining their bid. The opening spread shows children dancing on a beach beneath an enormous Brazilian flag, and, above a photo of wind surfers riding waves with a backdrop of Christ the Redeemer. The pages proclaim a new birth. "It is driven by sport, with athletes and the entire sports community looking forward to the lasting benefits the games will bring."

The brochure promises to change the economy, to educate children and even to protect the world's largest "urban forest." The obligatory quote from Pele is included. The document is full of maps and photos and plans, but there's no mention of the war on the hill that overlooks Maracana Stadium, where the opening ceremonies will be held.

The word "favela" never appears.

When worlds collide

The two Rios are on a collision course.

Part of the city is breathtaking, a place of shimmering beaches and dark, trendy restaurants with stars on the wall. Men wear fedoras without irony. Models strut down the Copacabana Boardwalk. White-linen tourists sip from coconuts. There is always music, from a boom box on the beach, from speakers inside an open-air bar. This is the Brazil of glossy brochures. This is where things like these two sporting events -- the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics -- are born, things over which the poor in the slums have no control but which will have immense power to change their lives. The citizens of Macacos don't know if the changes will be good, or if the changes ultimately will destroy them, or when or how their fate will come. A sporting event is like the volcano on Macacos' horizon: It is mysterious and, despite the citizens of Macacos taking great pains not to anger it, eruption is inevitable. When the Olympics and World Cup were announced, the volcano began smoking.

The favelas, Rio's guilty conscience, almost a thousand of them, overlook paradise but never, ever partake. Dense, urban slums with wretched educational opportunities, no social services, no police protection, they exist outside civilized society. Residents who live in the city don't go up the hill. It's possible to live a middle-class life without the violence of the slums affecting one's daily existence. But the violence is always there. In 2010, there were 4,798 murders in Rio. That's about a fourth the number of murders annually in the entire United States. (The U.S. population is about 300 million people. Rio has 6 million.) Favelas are desperate places, and they've been ignored since the first one popped up in 1897. Only now, some of them are close to venues for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games.

Rio has less than three years to fix a crisis a century in the making.

The clock is ticking.

A successful Olympics bid followed by a gang war

The hill overlooking Maracana Stadium gave the city's old problem a new face. Two weeks after the IOC awarded the games to Rio, in October 2009, a gang war erupted. The extreme violence in such close proximity to the Olympic announcement brought the two Rios into focus.

Five months after the shooting stopped, a helicopter flew high above the battle scene. The hill, a mile long and five miles around, curls like a frown. The edges slope hard toward the streets. Lush green grass and bushy trees cover most of the hill. Here and there, clusters of naked boulders jut out. You can see everything from up here: the middle-class neighborhood controlled by the police, the warring slums controlled by the gangs, and the stadium that has the cops and the drug-trafficking gangbangers in a showdown. The pilot swings around the three favelas tucked into the hill's slopes and crevices, flying over the switchbacks leading to the top, over the makeshift houses of red brick and rusted tin stacked atop each other, something wedged into every inch. Besides the soccer field where games are banned, there is an empty swimming pool; the drug dealers forbid it to be filled with water.

The two neighborhoods sandwiching Macacos -- Sao Joao and Mangueira -- are controlled by the Comando Vermelho (Red Command) gang, the most powerful drug traffickers in Rio. Macacos is run by the Amigos dos Amigos, or the ADA. Enemies surround Macacos, from ultraviolent business competitors to corrupt cops.

Maracana Stadium will host World Cup matches and the 2016 opening ceremony. Fans coming to the stadium will be able to see the hill a mile away, not to mention television cameras beaming the images to billions around the world. "The message they send to the world is: Rio is at war," says Ignacio Cano, a police violence researcher feared by law enforcement officials because he exposes so much corruption. "We cannot sell this model to people all over the world. 'Come to our war, and in the middle of the war, we're gonna show you some sporting competition?'"

The blades thump as the pilot swings around the slums. He won't fly closer, and he won't fly lower. In that October 2009 battle, CV gang members began firing at a police helicopter with anti-aircraft guns. The big shells ripped into the rotors, leaving the pilot fighting for control, looking down into the dense urban neighborhood for a safe place to crash.

Invasion!

The battle began with a phone call from a maximum security prison.

CV bosses sent the order: Invade Macacos.

CVers and other hired guns came from Mangueira. They came from Alemao. They came from seven different favelas, gathering in Sao Joao. A convoy of gunman in covered trucks, followed by at least nine cars and dozens of motorcycles, formed an invasion fleet, unimpeded by the law, flowing through the empty streets of one of the largest cities in the world. Other soldiers, police sources said, followed the thin trails along the back of the hill toward the white rock topped with the white cross. The invaders could see a glow from the two dozen or so light bulbs strung across the cross -- a beacon.

They arrived shooting.

As the gunshots subsided, residents heard shouting: "Macacos is red!" They huddled on their floors. Mario Lima, the president of the Macacos neighborhood association, hid in his bathroom with his family. His son would still have nightmares more than a year later. They all clung to each other; they could hear the gangsters on the other side of the wall. As windows shattered in the house, the Limas could hear the glass hitting the floor and the threats that followed. Finally, the CV moved on to another house. Lima called the police. He called 10 times, begging for help. None came.

Through the long night, the CV held the favela. Entire families fled, abandoning their homes. They brought only what they could carry. Mothers pushed strollers down the hill. Others carried babies wrapped in blankets in their arms. Citizens gathered at a jail at the bottom of the hill, heating toward riot, angry that the police seemed to be doing nothing. They lit tires on fire in the streets. They threw rocks at the jail.

A man hiding in his home wrote into the local paper's website: "Where are the police?"

You are what you shoot

Brazil's police forces have always treated the favelas as enemy nations. They use the vocabulary of war: invasions, troops, battles. Every few months, cops from the BOPE Elite Squad -- think Brazil's Navy SEALS -- locked and loaded, would storm a favela, killing as many drug dealers as possible before withdrawing. Popular culture celebrated these raids in best-selling books and blockbuster movies.

For residents, the first warning is almost always the gunshots. The police come in behind a protective curtain of bullets. People run toward their homes. If they can't get there, they dive through the first open door. Schools close. Stores close. Everyone hides. Bullets ricochet off concrete walls and fly through cheaper ones. They shatter windows. Some people are executed. Others get shot randomly. Wrong place, wrong time. Bad luck.

To be fair, these raids are terrifying for the cops, too. Dogs leap out of doorways, barking maniacally. Children scream. Doors slam. The smell of garbage and raw sewage overwhelms the senses. Chests heave and hearts pound from the fear and the steep vertical incline. SUVs rush away the wounded. Gangster snipers aim high-caliber weapons from the cubist towers of open windows. The world shrinks to the metal in your hands. Firing a rifle brings you back into contact with yourself: You feel the kick of the stock, hear the bang of the hammer, smell the powder, taste the cordite, see the dense, white smoke and the glimmer of sun off the ejecting cartridge. Brave cops look for muzzle flashes. Most fire blind, hot shell casings jingling onto the pavement.

Invasion II!

The next morning the sun rose, chasing away the shadows.

Cops marched up the hill. Even as the gangsters retreated, machine guns rattled and rifles popped. Residents huddled in a nearby park, wondering if they'd ever go home again. But, unexpectedly, the CV faded fast. It gave up position after position. It lost everything, even the cross. It fled down the back of the hill. Overhead, a police helicopter named Phoenix 3 circled, providing air support. Downtown Rio looked and sounded like a war movie.

One fleeing drug trafficker looked up and saw Phoenix 3, flying low. He aimed his .30 caliber. A stream of shells flew toward the chopper. One pierced the floor and hit the co-pilot in the foot. Others cut up the rotors.

Pilot Marcelo Vaz felt the shudder. He smelled the smoke. The other cops screamed. Vaz could hear them calling out their injuries. Burns. Gunshots. He focused, looking down through the smoke. All around, nothing but dense urban ghetto. If he crashed into the favela, people would burn to death. He needed a clear spot. Finally, he saw it: a soccer field, a patch of rich brown dirt surrounded by weeds. Its systems failing, Phoenix 3 was now more rock than aircraft. Only 90 seconds had passed. Vaz braced. His passengers braced.

Seconds later, everybody within earshot heard the loudest boom of the morning, a roaring explosion. They saw the thick, black smoke. Lima, the neighborhood association president, was horrified. He felt like the city was collapsing. This was the final act in a long drama. The end of the end. If gangsters can shoot down helicopters, he thought, everything is lost.

On the soccer field, the blue tips of the rotors poked at odd angles from the wreckage. It didn't look like a helicopter. It looked like someone had emptied a garbage truck of burning, crumpled paper. Two cops died on impact. The two pilots suffered minor injuries. The two cops who survived the landing suffered severe burns and were rushed to a hospital.

The people of Macacos knew what was coming now. They all did. It didn't matter who'd pulled what trigger.

Everyone in the favela was guilty.

Hungering for revenge

Down below, the CV raged. It had taken Macacos and then lost it. A city bus driver on the 284 route saw gunmen run out of a favela. They carried gasoline, a rifle and a pistol. They ordered everyone out. "Down, down," they shouted. "We'll set fire." The scene repeated itself throughout the rest of Rio: cars and buses burning, red flames and black smoke, until only chassis were left, smoldering.

"The police invaded the slum and gave it back to ADA," well-known gang war author Julio Ludemir explains. "The CV said, 'Bull----. I did everything perfect. It was a perfect crime. I took this symbol.' We don't have wars over drug spots. We have wars to take symbols. That war was very planned, and they won the war. They sent a sign to the city: 'Bull----, police.'"

That night, CV gangsters celebrated their temporary victory over ADA and the downing of the Phoenix 3 with a concert, a rave with underground rappers. A local newspaper breathlessly reported they partied with whiskey and cocaine. The Internet hummed with songs eulogizing both sides. A day passed. Lima prayed that the police would stay, that they would occupy the neighborhood and rid them of gangs forever. A second day passed. These were times of horror. That's the word he would use later. Horror.

On the third day, the Amigos dos Amigos returned. They vowed revenge.

Coming soon: more mindless violence

The police vowed revenge, too.

A cycle begins anew. Violence begets violence. Cops found a body, blue from a beating and perforated with bullet holes, in a shopping cart at the bottom of Macacos. That brought the death toll to at least 25, including a secretary, a mechanic and two bricklayers. Cause of death: bad luck. Police found a cache of weapons buried in the bushes of a nearby favela: two shotguns, an AK-47, a 9 millimeter submachine gun, a sword, a grenade, 3,000 rounds of ammunition, eight rifles, a .30 caliber pistol, three bulletproof vests, eight BOPE uniforms and, the biggest prize of all, the gun used to shoot down the helicopter.

Police funerals were held. Brazil mourned. One man killed in the helicopter crash was an only child and had been married just five months. Another had a 3-year-old daughter. His wife became ill several times during the funeral. A third officer, who suffered severe burns in the crash of the Phoenix 3, died a few days later. During his funeral, a helicopter dropped rose petals on the casket.

Cops held up widows and hugged children, comforted mothers and carried coffins. Then they went hunting. They shot at traffickers. They shot a housewife in the back. She died holding her 11-month-old daughter. The little girl was hit in the arm. They shot at everything that moved. In a slum to the east of Macacos, a week later, residents told local reporters, the police raided the home of an 18-year-old student. They beat and tortured him. They suffocated him with a plastic bag.

Macacos awaited its turn.

Answers, but not for Macacos

In the aftermath of the Macacos disaster, change was in the wind. The old way was broken. Everyone knew this. The government saw the collision course of the two Rios and, with the clock ticking, decided to do something different.

BOPE continued raiding favelas, only this time more cops followed, putting up permanent police stations, walking the streets. The occupation forces are called UPPs. This is Rio to those who believe sporting events can change lives. Cops patrolling occupied favelas now find children smiling at them.

"I can see the kids are happy," said Capt. Rosana Alves as she walked through a favela in early 2010. "They have a better future. Their future will be better than their past. This is priceless. The kids ask me to play PlayStation with them. When they come back from school, they give me a kiss. They call me Aunt Rosana."

Guessing which neighborhoods would be retaken next consumed Rio de Janeiro. Police could not be told until the last minute because of the corruption that runs through every layer of government, so gossip filled the halls of cop shops around the city. In Macacos, citizens waited their turn. Some yearned for protection. Others feared what would happen if the police came. Lima and a few others quietly reached out and begged for a UPP in Macacos. They did so carefully; if the gangsters found out, they would be killed. To Lima, it was a risk worth taking. Lima believes the shiny brochures.

In Macacos, some of the remaining ADA soldiers began slipping out, relocating. Police watchdogs saw a trend. As the government forces raided favelas in the South Zone, where the Olympic venues are located, the poorer North Zone -- the safe harbor for fleeing traffickers -- grew more violent, but that's a problem for later. Open warfare in the vicinity of television cameras is Public Enemy No. 1.

Tension filled Macacos. What would the future hold for them?

Would the cops storm their hill?

Would they stay, and for how long?

What would be gained in the battle?

What would be lost?

Angst and pessimism

An uneasy peace hangs over the favela through the summer.

Five months have passed since the helicopter was shot down. At the bottom of the hill, fruit stands crowd the sidewalk on the left. Across the street is a school that caught fire during the battle. The road curves up ahead, rising toward the cross at the top of the hill. The air feels thick. Humidity presses down. The tension is as palpable as the speed bumps and raw sewage drains that dot the road up toward the cross.

Spray-paint graffiti scrawls a welcome: "Irak." The buildings stand two or three stories high on the main strip. Wires form a canopy over the narrow street. Power wires. Phone lines. Red and blue ethernet cables. Crowds gather at intersections. Up ahead is a storefront, and through a gate lives a woman who's spent her adult life trying to help the people of this favela.

She works at a school in Macacos. Several months after this meeting, she'll panic and ask that her name not be used. She says she is not afraid of dying but of endangering the school where she works.

She's The Teacher.

Since the helicopter crashed, she's been doing the same thing as every resident of Macacos: waiting nervously. Lima is an optimist about the UPPs and their future; she is the opposite -- a devout parishioner in the church of real life. She's seen too much to believe in hope. There's a Bible open in front of her, turned to Ecclesiastes. The first verse quotes Solomon: "Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless."

A portrait of a favela in limbo

The Teacher educated many of the drug dealers who now run Macacos. She doesn't mess with them and they don't mess with her. They know she's responsible for what little civilization there is on the hill.

When she got to Macacos decades ago, the neighborhood was improbably worse. No running water, no electricity, no schools. Thanks to her and others like her, the community has managed to provide some of these things for itself. A few. "The sewage system doesn't work," The Teacher says. "In our kindergarten, the kids are stepping into feces. Every day, we have to clean the whole kindergarten because the sewage water invades it. The kids are getting sick."

If she provides order, the traffickers provide law. The other Rio stops at the bottom of the hill by the fruit stands. Up here, the drug dealers are judge and jury. Battered wives go to them for justice. The Teacher doesn't need a security system at the school; if anyone broke in, retribution would be swift and gruesome. The rules cover offenses large and small. A kid who danced with someone else's girlfriend had his hair cut off. A kid who started a fight had to carry rocks in the sun. Theft can be punishable by death. "Whenever somebody does something wrong," says a resident of Macacos who asked not to be named, "the drug traffickers will hold a trial."

The current kingpin is nicknamed Scooby. He's the one who swore revenge on the CV for the invasion. Underground rappers write odes to him and put them on YouTube. He once kidnapped several cops and tortured them. He likes to steal cars. Not long ago, newspaper pictures showed his Mercedes-Benz convertible that police had seized.

He and the other gangsters throw parties for kids, help out if someone is in need. They aren't the ones roaring up in armored vehicles and letting thousands of rounds go on full auto. Every time the police come in shooting, Scooby grows more powerful. "The population here lives in fear of the police," The Teacher says. "The police shoot without thinking. You can see all the windows that have holes from the bullets."

Law-abiding residents are caught in between the cops and the dealers.

"If you live in a community like we do, you always have to think twice," The Teacher says. "You have to be careful. You have to pretend you don't see what's going on. There is lots of fear dominating this community. For example, you coming here to do an interview. Depending on what I say in this interview, there is the possibility that something might happen. From both sides. Police and the drug dealers.

"One former president of the neighborhood association had to leave this community because of an interview he did. He lived for many years in the community. He had a house here and a family. He gave an interview. The drug dealers didn't like it. They burned his house. And he had to go away with his family. Because of one interview he gave. It's really dangerous to have a position. To tell the truth. You can't trust anyone."

Or anything, even the future. Upstairs at the school where The Teacher works, in the corner of a computer lab, one young man who can't be older than 12 hunches over a screen. He's playing an urban war game -- a virtual version of the real thing happening outside these walls -- and on the screen, he's picking his weapon, from a pistol all the way up to a chain gun. He's seen most of these weapons in the favela. A local charity worker said her 9-year-old students play a twisted urban game: Whoever takes the cell phone picture of the most shocking scene wins.

Students who aren't in gangs borrow guns from students who are. Girls like guys with guns. Kids from Macacos can't go to school with kids from Mangueira or Sao Joao. Not long ago a nongovernmental charitable organization with mission schools in Macacos and Mangueira managed to organize a trip to Rio's Museum of Modern Art. It gathered students from both favelas and prepared to show them the possibility of manicured gardens and priceless masterpieces. The teachers wanted them to stand side by side, not as enemies but as friends, and see there could be beauty in the world.

This is Rio in real life: The NGO had to use separate buses.

Finally, it's Macacos' turn

That was then, this is now. A year after the helicopter was shot down, the residents of Macacos heard the news.

They were next.

On Thursday, Oct. 14, 2010, almost 200 cops charged the hill, from the bottom and from the back, converging on the cross. They found all the ADA gangsters gone, having fled the night before after being tipped off about the impending raid. Not a shot was fired.

People came out of their houses into the light. Lima saw his neighbors happy. They were happy to see police. He couldn't believe it. For years, they'd seen cops raid and seen friends die and seen drug dealers return as soon as the police left. But this was different. "Now we know that the police will stay," he says. "At least for four years."

The cops began organizing a soccer tournament for the long-abandoned field. A UPP was set up, and the officers were welcomed by the neighborhood. "It was one year full of frustration," Lima says. "We thought that the police would never come. The government kept announcing the occupation of other areas, but why didn't they come here? And our situation was much more difficult than in other areas."

Leonardo Novo is a BOPE commander. His job is dangerous, and his father stays awake every time his son works nights, sleep not coming until he knows his boy is alive. Novo, who looks young -- maybe it's the braces on his teeth -- is one of the peacekeepers in charge of Macacos. Four units work 24-hour shifts, keeping familiar faces on the streets. Several months ago, Novo walked from his base near the spot where people were once burned alive, making his way past the cross and on down the hill.

"The people here don't trust the police," he says. "They fear that the police will leave and the ADA comes back.

"That won't happen."

Still, fear remains. The cops sense it. The people know it. "I will give you an interview in 50 years," one resident says, "when I am sure that everything went right! Until then, everybody keeps their mouth shut."

But now, at least, there is hope. The two Rios are colliding and, in some places, a new Rio is arising. There are signs everywhere, including the middle of Macacos.

The swimming pool is full of clear, blue water.

A dozen kids paddle around, laughing, and more run along the sides, ready to jump in. The once tense air of the favela is filled with the splashes of children at play.

Free, but for how long?

The Teacher is still afraid.

The gangsters aren't dead. They've just moved. The cops expected to find as many as 50 heavy guns. They found none. The Amigos dos Amigos took their firepower with them, joining with other fleeing gang members, waiting. Family members of gang members remain in Macacos, eyes on the ground. ADA spies sneak in and out. They want to know who is giving interviews and who is cooperating with the police.

Scooby is thought to be in a favela called Rocinha.

What if the cops leave Macacos when the Olympics are over? It's happened before. Ludemir, the gang war journalist, described a government program in the '90s in which cops flooded selected favelas. Soon the government tired of this strategy, removed all the cops and, as Julio says, "It all went back to s---."

"It won't be forever," The Teacher says. "It will only be for a short time, because it's too expensive for the government to maintain. So maybe they put in the police unit just for the Olympic Games, so that there will be peace during the Olympic Games, then if they run out of money, they leave. Everything will go back to normal. When police leave, the dealers will come back and everyone who cooperated will be shot."

The sun hangs low and hot. She stands outside the school. There are now smiling cops in her favela, and a soccer field used for games instead of killing, and water in the swimming pool. But the favela itself remains, rising around her: the patchwork homes, the gang graffiti, the chicken-wire windows. The city below remains, like the volcano in reverse, ready to change their lives on a whim. She faces the cross at the top of the hill. Meaningless. That's what King Solomon said. Olympics come and go. Governments get bored. Maybe the devil you know is better than the one you don't.

"Much better," she says.

She doesn't believe in shiny brochures, only Rio in real life.

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com. You can find his story archive here.

Follow ESPN_Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader.

Join the conversation about "Deadly Games."