Summary: A brain training audiogame makes it possible to hear speech in noisy backgrounds with greater ease, a new study reports.

Source: Cell Press.

For many people with hearing challenges, trying to follow a conversation in a crowded restaurant or other noisy venue is a major struggle, even with hearing aids. Now researchers reporting in Current Biology on October 19th have some good news: time spent playing a specially designed, brain-training audiogame could help.

In fact, after playing the game, hearing impaired elderly people correctly made out 25 percent more words in the presence of high levels of background noise. The training provided about three times more benefit than hearing aids alone.

“These findings underscore that understanding speech in noisy listening conditions is a whole brain activity, and is not strictly governed by the ear,” said Daniel Polley of Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School. “The improvements in speech intelligibility following closed loop audiomotor perceptual training did not arise from an improved signal being transferred from the ear to the brain. Our subjects’ hearing, strictly speaking, did not get better.” And, yet, their ability to make sense of what they’d heard did.

Those improvements reflect better use of other cognitive resources, including selective auditory attention, Polley explained. In other words, participants were better able to filter out noise and distinguish between a target speaker and background distractions.

The study enrolled 24 older adults, at an average of 70-years-old. All participants had mild to severe hearing loss and had worn hearing aids for an average of 7 years. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two training groups. Members of both groups were asked to spend 3.5 hours per week for 8 weeks playing a game. One group played a game designed with the intention of improving player’s ability to follow conversations. It challenged them to monitor subtle deviations between predicted and actual auditory feedback as they moved their fingertip through a virtual soundscape. As a “placebo” control, the other group played a game that challenged player’s auditory working memory and wasn’t expected to help with speech intelligibility.

The study was designed so that the 24 participants and the researchers did not know who trained with the audiogame programmed for therapeutic benefit and who trained with a “placebo” game without therapeutic intent. Participants from each group reported equivalent expectations that their speech understanding would be improved.

People in both groups improved on their respective auditory tasks and had comparable expectations for improved speech processing. Despite those expectations, individuals that played the working memory game showed no improvement in their ability to make out words or even improvements on other working memory tasks. The other group showed marked improvements, correctly identifying 25 percent more words in spoken sentences or digit sequences presented in high levels of background noise. Those gains in speech intelligibility could also be predicted based on the accuracy with which those individuals played the game.

Those benefits didn’t persist in the absence of continuing practice, the researchers report. However, they say, the findings show that “perceptual learning on a computerized audiogame can transfer to ‘real world’ communication challenges.” Polley envisions a time when hearing challenges might be managed through a combination of auditory training software coupled with the latest in-ear listening devices.

“We look forward to a future where auditory perceptual training software that has been inspired by principles of brain plasticity, not audiological testing, is packaged with new advances in these listening devices,” he said. “There is reason to believe that the sum of these benefits would be greater than could be expected from any one approach applied in isolation.”

Funding: The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant no. P50DC015857 and a research grant from the One Fund Boston.

Source: Joseph Caputo – Cell Press

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

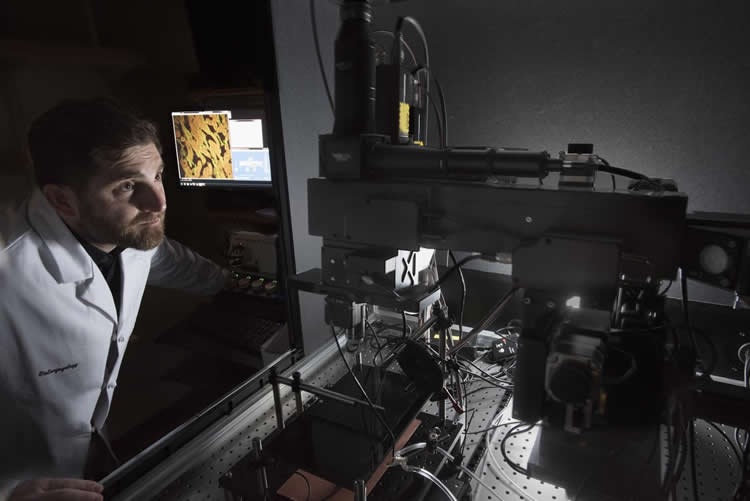

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to John Earle / Mass. Eye and Ear.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Audiomotor Perceptual Training Enhances Speech Intelligibility in Background Noise” by Jonathon P. Whitton, Kenneth E. Hancock, Jeffrey M. Shannon, and Daniel B. Polley in Current Biology. Published online October 19 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.014

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Cell Press “Brain training Can Improve Understanding of Speech in Noisy Places.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 19 October 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/speech-noise-brain-training-7776/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Cell Press (2017, October 19). Brain training Can Improve Understanding of Speech in Noisy Places. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved October 19, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/speech-noise-brain-training-7776/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Cell Press “Brain training Can Improve Understanding of Speech in Noisy Places.” https://neurosciencenews.com/speech-noise-brain-training-7776/ (accessed October 19, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Audiomotor Perceptual Training Enhances Speech Intelligibility in Background Noise

Highlights

•Elderly subjects trained for 8 weeks on a computerized audiomotor interface

•Speech-in-noise intelligibility in challenging listening conditions improved by 25%

•Generalized training benefits were compared to and exceeded placebo effects

•Inhibitory control ability and game strategy predicted individual training benefits

Summary

Sensory and motor skills can be improved with training, but learning is often restricted to practice stimuli. As an exception, training on closed-loop (CL) sensorimotor interfaces, such as action video games and musical instruments, can impart a broad spectrum of perceptual benefits. Here we ask whether computerized CL auditory training can enhance speech understanding in levels of background noise that approximate a crowded restaurant. Elderly hearing-impaired subjects trained for 8 weeks on a CL game that, like a musical instrument, challenged them to monitor subtle deviations between predicted and actual auditory feedback as they moved their fingertip through a virtual soundscape. We performed our study as a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by training other subjects in an auditory working-memory (WM) task. Subjects in both groups improved at their respective auditory tasks and reported comparable expectations for improved speech processing, thereby controlling for placebo effects. Whereas speech intelligibility was unchanged after WM training, subjects in the CL training group could correctly identify 25% more words in spoken sentences or digit sequences presented in high levels of background noise. Numerically, CL audiomotor training provided more than three times the benefit of our subjects’ hearing aids for speech processing in noisy listening conditions. Gains in speech intelligibility could be predicted from gameplay accuracy and baseline inhibitory control. However, benefits did not persist in the absence of continuing practice. These studies employ stringent clinical standards to demonstrate that perceptual learning on a computerized audio game can transfer to “real-world” communication challenges.

“Audiomotor Perceptual Training Enhances Speech Intelligibility in Background Noise” by Jonathon P. Whitton, Kenneth E. Hancock, Jeffrey M. Shannon, and Daniel B. Polley in Current Biology. Published online October 19 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.014