At the 2014 Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, Jan Koum, chief executive of WhatsApp, made an announcement that would cause much unease 4,000 miles away in New Delhi. “We want to make sure people always have the ability to stay in touch with their friends and loved ones really affordably,” he said. “We’re going to introduce voice on WhatsApp in the second quarter of this year.”

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

India’s telecom operators were less than enthusiastic about this announcement.. With more than 70m users in India, the instant messaging platform has emerged as one of the most popular alternatives to conventional text messaging – enough to make telecom operators jittery.

It isn’t surprising then that at the same event, India’s telecoms operators made it clear that they wanted a revenue-sharing agreement with internet companies. They believed that services such as WhatsApp’s voice-calling feature would potentially cut the revenue generated by voice calls and text messages.

In essence, telecom operators wanted the internet to be mouldable, to be shaped in any way they liked. After all, India is one of the world’s fastest-growing internet markets, with 851m connections according to Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) figures .

Telecom companies know this and profit from the internet services they provide to mobile phone users. For instance, major Indian networks like Airtel added 7.46m 3G internet connections, Vodafone 11.4m and Idea Cellular 7.1m in the past four quarters, according to Medianama.com. Yet they want greater control of how people use the internet on mobile phones.

On 27 March, the telecoms regulator released a “consultation paper” in which it made a series of recommendations to deal with the growth of internet services and apps. The key cornerstones of this 118-page minefield of legalese and jargon advocate the licensing of internet companies, along with killing the network neutrality that exists in India today.

‘Pay up or be throttled’

Nikhil Pahwa, editor of Medianama.com, says: “Either you will have licensing of all internet companies if they want to be available in India – whether those companies are operating out of India or abroad. Or the same rules [that govern telecom companies] will apply to anything that involves any form of communication such as messaging or voice. So any service which uses either voice or messaging will need to buy a licence.”

The regulator also recommended that internet companies register themselves with telecom operators to ensure smooth service delivery to users. “So effectively, there would be a splintered version of the internet, where one part will be that companies become vendors of telecom operators. For that, they’ll have to pay and [in return] they will receive certain privileges,” Pahwa explains. “Those who don’t pay for these privileges will then be throttled or they will be made more expensive – or they may be blocked.”

That means a telco like Airtel could sign a deal with WhatsApp, offering it for free and slowing down, blocking access to or increasing the price of Apple’s iMessage service or similar third-party apps such as WeChat.

As this was a public consultation paper, Indians were asked to give their views on its recommendations to the telecoms regulator by 24 April. Pahwa and a group of like-minded friends saw an opportunity to prevent control of the internet being handed to the big telcos.

Soon after the consultation paper was released, Pahwa became part of a coalition of more than 50 artists, journalists, techies and lawyers who started Save The Internet – an online campaign that urged Indians to send in their suggestions of ways to preserve net neutrality to the regulator . They created a list of answers to the 20 questions the regulator posed in its consultation paper that users could copy, paste and email to it in just three clicks.

Initially, public response was muted, but all that changed on 11 April, when AIB, a popular comedy troupe, made a video simplifying network neutrality and highlighting how the regulator’s recommendations could have an adverse effect on internet usage in India. The strategy seemed to have been inspired by Jon Oliver’s 13-minute sketch that urged Americans to visit the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) website and demand net neutrality. Like its American cousin, this strategy too was successful.

By the time 24 April arrived, 1.1 million Indians (including this writer) had emailed the TRAI, urging it not to license what it called “over-the-top”, internet-based services, nor to give telecom operators the legal sanction to start “zero-rating” plans – or charging different prices for different services.

Media companies such as NDTV, Times Internet and NewsHunt, as well as travel portal Cleartrip, all announced that they were leaving Internet.org, Facebook’s controversial effort to offer selective internet access to those hitherto without it. Tathagata Satpathy, an MP from the Biju Janata Dal party of Orissa, wrote a strongly worded letter of dissent to the telecoms regulator , saying that its recommendations would allow “big companies to form monopolies over the mobile web”.

But the consultation paper of March was only one step in a concerted effort by telecom operators to fundamentally alter the way Indians use the internet. In December 2014, the website TelecomTalk reported that Airtel had started charging users an additional amount for calls made via apps like Skype and Viber, over and above the data packs they had subscribed to. Once Airtel’s violation of network neutrality was revealed, the company backtracked and said it would wait for the regulator’s consultation paper.

“I read this differently from most people,” Pahwa recalls. “Most people said that ‘users have won’ because consumers had asked for this to be withdrawn. My reading was that the only reason why it had been withdrawn was because the TRAI agreed to do a consultation. In effect, it had been forced to do a consultation.”

In January 2015, Medianama also reported that Rajan Mathews, director general of the Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI), had written a letter to TRAI chairman Rahul Khullar in December 2014, asking for WhatsApp to be licensed – a demand that became a “recommendation” in the regulator’s consultation paper. So why did TRAI act in the manner that it did? We made multiple attempts to reach its representatives but no one was available to respond.

Cost of access

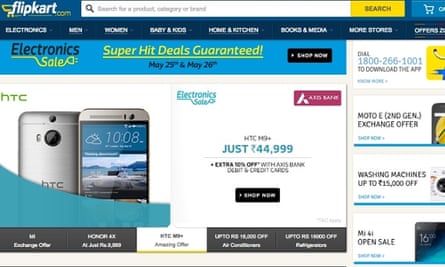

The global definition of net neutrality stops at advocating an internet that is equal for all. But in the Indian context, there is an additional dimension – zero-rating services. That refers to consumers’ data packs being subsidised either by their telecom service providers or by the app/service they are accessing. For instance, Flipkart, the Indian e-commerce giant, signed a deal with Airtel to “zero-rate” its services on Airtel’s platform.

The deal was severely criticised for creating an unequal playing field. While Flipkart could afford to pay Airtel, a smaller start-up would not be able to. Once the net neutrality debate in India gained momentum, Flipkart decide to scrap this arrangement. “In India, zero-rating is far more important because it isn’t about slow lanes and fast lanes,” explains Pahwa. “It’s about cost of access and whether some sites are being made cheaper than others and, therefore, some sites being made more expensive than others. All of this influences a consumer’s decision whether to access a service or not.”

For their part, the COAI claims that it too believes in giving users equal access to the internet and not throttling traffic. How, then, does it justify its members offering zero-rating services? “It’s a misunderstanding of what Airtel did,” says the COAI’s Mathews. “Airtel provided a non-discriminatory platform to anybody who wanted [it] as an application provider. This is not for regular customers. It’s only for qualifying applications to put them on mobile networks and the internet. So what Airtel did was provide free access to service providers. There was no discrimination and it was equal.”

In its counter-comment submission to the telecoms regulator, the COAI has asked for zero-rating services to stay in the interest of “social welfare”. “Programs like zero-rating, which we call subsidised calling plans, are intended to get people who have never used the internet, who have not become familiar with it, who have very sensitive price points [to], in a subsidised manner, try to come on to the internet,” adds Mathews.

The COAI has also argued that services like WhatsApp are the same as regular voice calls and text messaging and thus deprive mobile operators of revenue. Hence, they argue they should be allowed to charge users extra to access such apps. On both counts, the industry body seems on shaky ground.

Not a luxury but a necessity

In its counter-comment submissions to the TRAI, Medianama.com has said that Airtel, Vodafone, Reliance and Idea, India’s top four telecom operators, have added 8.5 million users. Moreover, Airtel’s average revenue per user (ARPU) from data services increased by a record 13.3% quarter-on-quarter. Data revenue for Idea Cellular rose 5.9%.

This unprecedented campaign to protect net neutrality in India underlines the importance of the internet. For millions of young Indians today, the internet is not a luxury but a necessity. In a country rife with political, social and economic inequalities, the web is a liberating universe that flattens hierarchies, creates room for innovation and allows unadulterated and totally free expression of speech. It is a reason why some of India’s most successful startups also have called for the internet to be kept neutral.

What also helped was a sustained effort by the Save The Internet coalition, during which they turned TRAI’s 118-page minefield into a 23-page easy-to-comprehend document. (According to Pahwa, India’s MPs have chosen to read this rather than the original paper). In Bangalore, his colleague Kiran Jonnalagadda helped run the Save The Internet website and set up the @bulletinbabu Twitter account – a live counter of emails sent to the regulator. They also drafted a letter citizens could send to their local MPs, urging them to support net neutrality. “These consultations are only public for the name of it,” Pahwa added. “They’re not public consultations – we helped make this a public consultation.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion