The private equity business model is pretty simple. First, convince some wealthy people and institutions that you’re so smart that you deserve their money. Then, take some of that money, add a hefty helping of debt, and buy an undervalued company. Quickly fix it up using your superior smarts—or by firing lots of people and cutting other costs to the bone. As quickly as possible, sell it on at a profit to another company, or cash out via an IPO. Take a big cut of the proceeds as a fee and return the rest to your backers. Repeat.

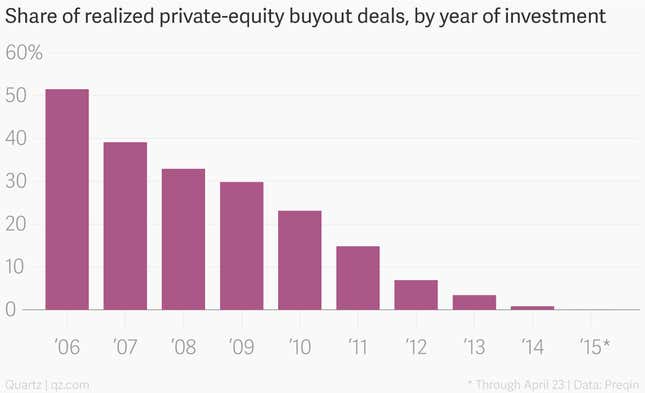

In real life it’s hardly that simple, of course. Just ask any of the firms that are still stuck holding companies they bought in the bubbly days before the 2008 financial crisis. New data from Preqin (pdf), a research firm, shows that only half of private-equity buyouts made in 2006 have since been sold:

Typically, private equity firms want to get rid of their acquisitions within five years, at most. Suffice to say that the firms still sitting on purchases from 2006 are not too happy about it. But that’s what happens a business model that relies mostly on frothy valuations and mountains of debt meets a cratering global economy and financial market on the fritz.

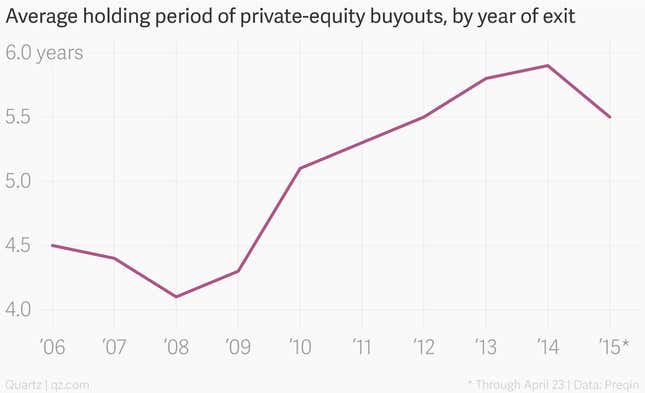

But as economic conditions continue to improve, the average holding period for private equity investments has finally started to shorten again, marking a “significant milepost,” according to Preqin:

The faster churn is due only partly to buoyant markets making IPOs more attractive and to cash-rich companies growing keen on acquisitions. A third of recent exits have been only partial ones, and a third were sold to other private equity firms. In these so-called “pass the parcel” deals, the portfolio companies that have worn out their welcome with one firm simply become another firm’s problem.