The Low-Tech Appeal of Little Free Libraries

The "take a book, return a book" boxes are catching in even on places where Kindles and brick-and-mortar books abound.

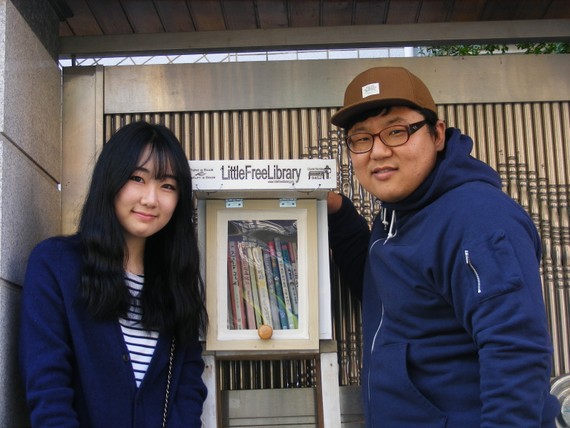

When a 36-year-old bibliophile in Daegu, South Korea, sat down at his computer and googled the word “library,” he didn’t expect to find anything particularly noteworthy. But as DooSun You scrolled through the results, an appealingly anti-tech concept popped up.

The Internet led him to Little Free Libraries—hand-built boxes where neighbors can trade novels, memoirs, comics, and cookbooks, and connect with each other in the process.

The little libraries immediately appealed to DooSun. “Reading books is one of the most valuable things in my life. I think a book is equal to a treasure,” he says. “I hoped to share that feeling with my neighbors—that’s the reason I wanted a Little Free Library.” The website showed pictures of the diminutive structures standing in front yards, on city curbs, and alongside country roads all over the world, along with their GPS locations. “The Little Free Library map was a treasure map,” he says.

Soon after his online discovery, DooSun built a Little Free Library—the first one in South Korea—in front of his apartment building. Then he built a second at a different spot. Then a third. Slowly, his “take a book, return a book” libraries began bringing people together, garnering book donations and handwritten notes of thanks from strangers. He now pastes a QR code on the front of each library, so passersby can use their smartphones to learn more about them, and he regularly exchanges emails with others who want to build their own. He recently started a Facebook group where other Little Free Library stewards throughout Asia can swap ideas and experiences—as easily as visitors to their libraries swap physical books.

In 2009, Tod Bol built the first Little Free Library in the Mississippi River town of Hudson, Wisconsin, as a tribute to his mother—a dedicated reader and former schoolteacher. When he saw the people of his community gathering around it like a neighborhood water cooler, exchanging conversation as well as books, he knew he wanted to take his simple idea farther.

“We have a natural sense of wanting to be connected, but there are so many things that push us apart,” Bol says. “I think Little Free Libraries open the door to conversations we want to have with each other.”

Since then, his idea has become a full-fledged movement, spreading from state to state and country to country. There are now 18,000 of the little structures around the world, located in each of the 50 states and in 70 countries—from Ukraine to Uganda, Italy to Japan. They’re multiplying so quickly, in fact, that the understaffed and underfunded nonprofit struggle to keep its world map up to date.

Khalid and Yasmin Ansari, who live in Qatar, say they get a special satisfaction out of seeing their six-year-old son Umayr’s Little Free Library represented on the website. “When looking at the LFL world map,” says Khalid, “you almost feel obliged to have one in the neighborhood to fill the gap. It's like doing your part in your part of the world.”

In some places, Little Free Libraries are filling a role usually served by brick-and-mortar libraries; the organization’s Books Around the Block program, for example, aims to bring LFLs to places where kids and adults don’t have easy access to books. In North Minneapolis, an area more often in the news for shootings than community engagement, the Books Around the Block initiative set up 40 of the little libraries. Two hundred more sprung up shortly thereafter.

Last year, Sarah Maxey of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, discovered Little Free Libraries when browsing the crowdfunding site Kickstarter. She was then inspired to launch her own LFL Kickstarter campaign. The response was enthusiastic: By the time the campaign ended, Maxey had raised more than $10,000 for her cause—enough money to build dozens (and dozens) of little libraries.

“What happens is, you start the momentum, and then the community—the Lions Club, the Rotary, the churches, the neighbors—steps up and builds more. It just keeps going,” Bol says.

Individual stewards are using their Little Free Libraries in altruistic ways, too. Tina Sipula of Clare House, a food pantry in Bloomington, Illinois, does more than distribute groceries; she distributes books via an on-site Little Free Library. As she points out, homeless people don’t have addresses—which means they can’t get public library cards. Linda Prout was instrumental in bringing dozens of Little Free Libraries to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and Lisa Heydlauff of Bihar, India, is working to bring a thousand Little Free Libraries to girls’ schools in her country, filling them with books that teach business and entrepreneurial skills.

“Little Free Libraries create neighborhood heroes,” says Bol. “That’s a big part of why it’s succeeding.”

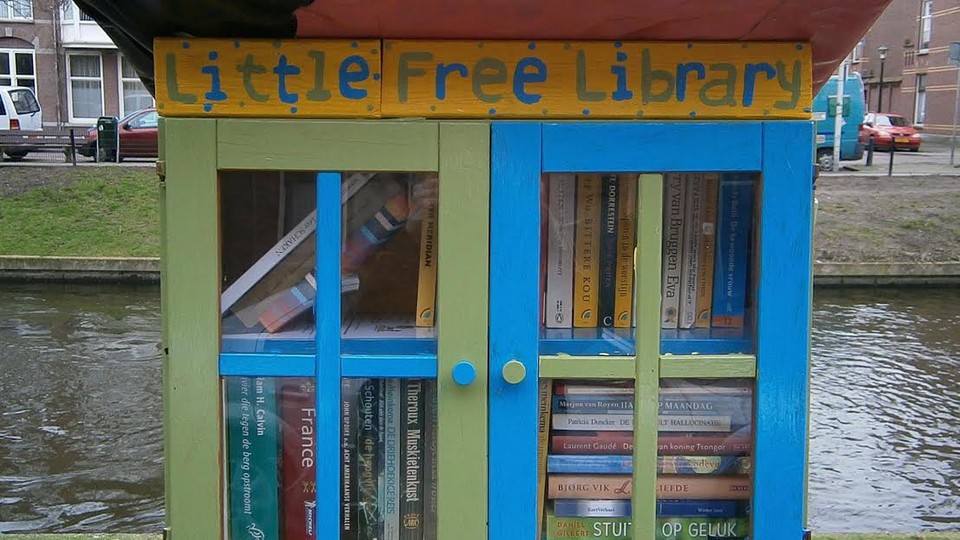

Though they owe their spread largely to the Internet, Little Free Libraries often serve as an antidote to a world of Kindle downloads and data-driven algorithms. The little wooden boxes are refreshingly physical—and human. When you open the door, serendipity (and your neighbors’ taste) dictates what you’ll find. The selection of 20 or so books could contain a Russian novel, a motorcycle repair manual, a Scandinavian cookbook, or a field guide to birds.

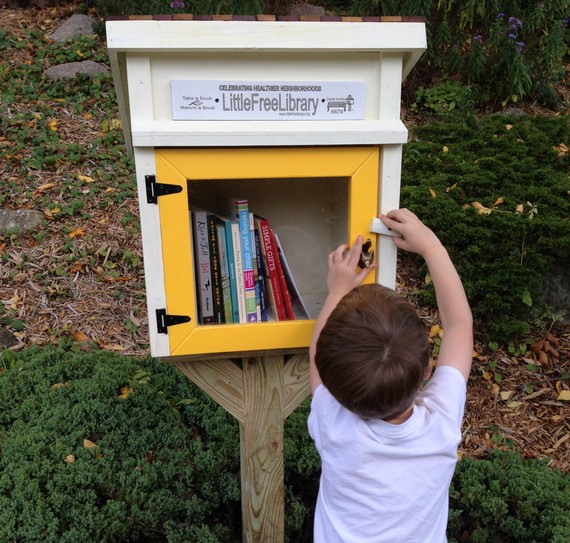

For many people—particularly in more affluent areas where libraries abound—this sense of discovery is an LFL’s main appeal. A girl walking home from school might pick up a graphic novel that gets her excited about reading; a man on his way to the bus stop might find a volume of poetry that changes his outlook on life. Every book is a potential source of inspiration.

Added to that is a kind of literary voyeurism, in which visitors get to contemplate the reading habits of their neighbors. Who left the Brazilian travel guides, and who’s reading Camus? Who added Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, my favorite novel of the last five years? And where will my copy of The Odyssey end up when I leave it in the library for someone else? By peeking into the reading lives of fellow Little Free Library users, you get to know your block better.

“I think it warms peoples' hearts that a stranger would go through the trouble to leave a gift for passersby,” says Suzanne Pettypiece, steward of a Brooklyn Little Free Library—the first one in New York. “And everyone knows books are magical, so when you build a little house for them and say, ‘Hey, take one of these, because we think you'll like it’—well, that's kind of exciting.”

Some people use Little Free Libraries specifically to share something about themselves, says founder Todd Bol:

After all, no matter how closely a computer studies your search habits, its algorithms will never have the charm and mystique of a simple wooden box filled with a neighbor’s literary treasures. It won’t be able to lend you a cup of sugar either.