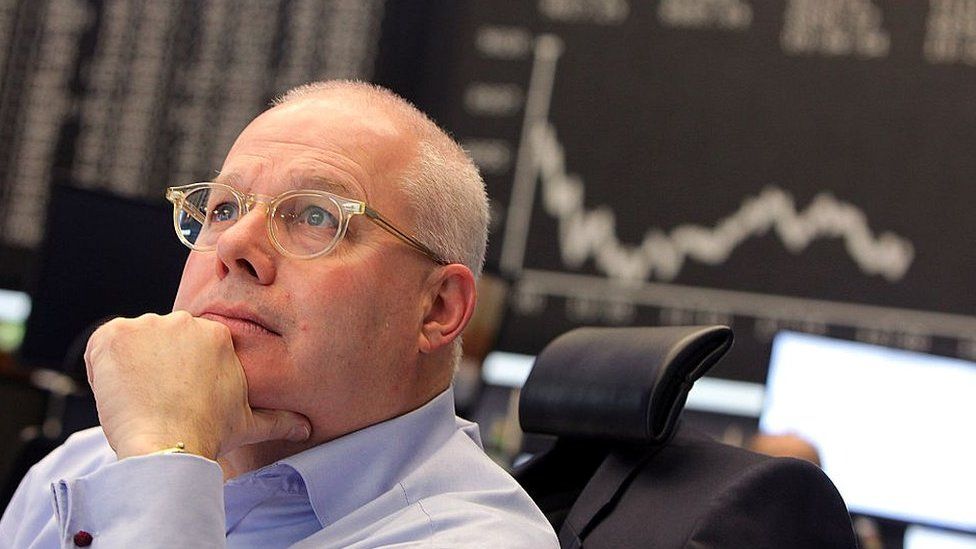

Is Germany dragging down the eurozone?

- Published

New eurozone economic figures released today have shown continued, if rather sluggish growth, with significant variation between countries.

Germany is in line with that: growth but not very strong. Both Germany and the eurozone as a whole have come in at 0.3% growth for the final three months of last year.

But has Germany, which is the eurozone's largest economy, actually been a drag on the region more widely?

There is an argument that Germany's large and persistent pattern of exporting far more than it imports is holding back the whole eurozone.

The context for this is the eurozone financial crisis.

To understand why some regard Germany as a problem we need to start with the countries that were most hit by the financial storms.

Several have had to make difficult and unpopular adjustments: austerity to improve government finances and economic reforms to enhance growth in the longer run.

Political strains

Many economists say austerity has been a headwind holding back the recovery, although there is a contrary view that it can sometimes support a return to growth.

Whatever the economic arguments, there have certainly been political strains.

Several eurozone governments following austerity policies have faced protests on the streets and at the ballot box.

But could it have been a little easier?

That is where Germany comes in. There certainly is a view that Germany has in effect made it harder than it need have been.

How so? Germany surely is the seat of eurozone financial prudence and virtue? Well, there is a case that those features of Germany are a problem for the others.

Here's why.

Economic imbalances

The most obvious features of the eurozone crisis were banks under strain, governments struggling to borrow and housing market busts in some countries.

But there were also massive trade and financial imbalances between countries.

In the years before the crisis the countries most severely hit ran increasingly large deficits in what's called their "current accounts".

That includes exports and imports of goods and services and a limited range of financial transfers.

A deficit like that needs to be financed by funds from abroad. When things were going well that was easy enough.

Foreign banks lent money and investors bought financial assets, including government bonds or debt, which is in effect lending money.

But that process was severely disrupted by the eurozone financial crisis as the soundness of banks and governments in the crisis countries came to be questioned.

They had to adjust. With those financial flows disrupted they had to have lower current account deficits, or even surpluses. And they have.

All the eurozone countries that received bailouts had large current account deficits ahead of the crisis.

In Greece, Portugal and Cyprus it peaked at somewhere between 12-15% of national income or GDP. In Spain it was close to double figures and in Ireland a still hefty 5.7%.

All now have a surplus except Cyprus where the deficit has declined.

Germany's growing surplus

Now here's an important piece of economic arithmetic. For the whole world, current accounts must balance - a surplus in one is balanced by a deficit somewhere else.

It follows that the change from deficit to surplus in Greece, Portugal and the others must be reflected in a move in the opposite direction in other countries.

The obvious place to look for that is within the eurozone, to those countries that had surpluses ahead of the crisis.

That includes Austria, Finland and the Netherlands. But the really big one was, you might have guessed, Germany.

So has Germany's surplus declined as the crisis countries adjusted? No, it has got bigger, from 5.6% of GDP in 2010 to 8.5% last year.

There has been an adjustment corresponding to the new surpluses in Greece and others. But it's outside the eurozone.

In 2010, the eurozone was more or less in balance with the rest of the world now it has a substantial surplus.

To put it the other way round, the rest of the world now has a hefty deficit with the eurozone.

Many argue that it would have been easier for the crisis countries to adjust if Germany's surplus had fallen.

What that would have meant in practice is that Germany would have bought more goods and services from the rest of the eurozone.

Germany's persistent and even rising current account surplus means that the burden of adjustment has fallen largely on the crisis countries so that they import less than they would otherwise have done.

In fact there have been some marked falls in imports, in the case of Greece for five consecutive years.

Perhaps with a stronger demand from Germany they would have been able to grow quicker, which in turn might have helped repair their government finances more quickly and had less adverse an impact on living standards.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of the Daily Telegraph is especially critical: "The surplus is …surely more dangerous for eurozone unity than anything going on in Greece."

'Excess savings'

To be clear this is not a case of criticising German industry for producing high quality goods that others want to buy.

Daniel Gros of the Centre for European Policy Studies explains: "A strict economic view of the situation would be different: the large current account surplus reflects an excess of domestic savings over domestic investment."

This is a central point.

A current account balance is related to the government finances - a government deficit tends to push the current account towards deficit - and also the amount that a country saves and invests.

If you save more than you invest and if the government spends less than it gets in tax, you have a current account surplus.

So one option would be for the German government to spend more, or tax less. Could it afford to do so? It has had a surplus in its finances since 2012 and the burden of accumulated government debt is not particularly large.

Daniel Gros suggests that there's a case for more public investment in infrastructure. Some in Germany even use expressions like "crumbling infrastructure". It must seem an exaggeration to most foreign visitors, but there is an active debate.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of the Daily Telegraph is more acerbic: "The sooner Germany abandons fiscal fetishism and invests its own money in its own country for its own good, the better it will be for everybody."

The idea being that if Germany saved less some of the extra spending would go abroad - on imported goods, paying workers who might take foreign holidays or foreign workers might be employed who would send some money home.

Budgetary defence

Still, the German surplus is often seen as a sign of the country's economic prowess.

Jens Weidmann, president of the Germany's central bank, the Bundesbank, called the country's balanced government budget a success.

"It would be absurd to discuss measures aimed at artificially weakening Germany's competitiveness in order to reduce current account surpluses vis-a-vis the other euro-area countries."

The scale of Germany's surplus does also reflect the fact that it, like the rest of the eurozone has had some benefit from the recent weakness of the euro, improving its competitiveness.

Whatever the reasons, and however you allocate any blame, it's likely the figures coming soon will show a recovery in the eurozone that's still distinctly lacking in vigour.

- Published11 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published4 February 2016

- Published2 February 2016

- Published18 January 2016