Was just scrolling through the ever fascinating Chillifrog and came across this post on The Crystal Palace, which has borrowed it’s words from Bill Bryson’s presumably equally fascinating At Home. I remember first reading about this in first year and it still stands as one of those buildings that first amazes me, then ultimately frustrates me due to its non-existence. (although, it could be the fact that it’s because it only exists in the form of some grainy photos and whimsical illustrations that makes it so fascinating)

The Crystal Palace.

“The Crystal Palace of London, one of the greatest architectural triumphs of the nineteenth century, the largest building in the world at its completion, and a building whose design influence remains pervasive even today:

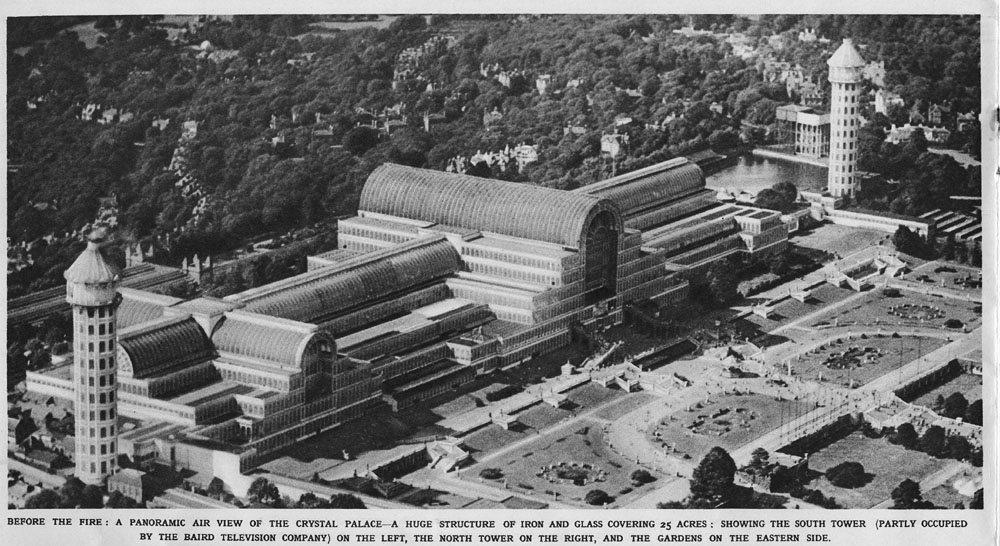

“In the autumn of 1850, in Hyde Park in London, there arose a most extraordinary structure: a giant iron-and-glass greenhouse covering nineteen acres of ground and containing within its airy vastness enough room for four St. Paul’s Cathedrals. For the short time of its existence, it was the biggest building on Earth. Known formally as the Palace of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, it was incontestably magnificent, but all the more so for being so sudden, so startlingly glassy, so gloriously and unexpectedly there. Douglas Jerrold, a columnist for the weekly magazine Punch, dubbed it the Crystal Palace, and the name stuck.

“It had taken just five months to build. It was a miracle that it was built at all. Less than a year earlier it had not even existed as an idea. The exhibition for which it was conceived was the dream of a civil servant named Henry Cole. … In 1849, Cole visited the Paris Exhibition - and … persuaded many worthies, including Prince Albert, to get excited about the idea of a great exhibition [for London], and on January 11, 1850, they held their first meeting with a view to opening on May 1 of the following year. This gave them slightly less than fifteen months to design and erect the largest building ever envisioned, attract and install tens of thousands of displays from every quarter of the globe, fit out restaurants and restrooms, employ staff, arrange insurance and police protection, print up handbills, and do a million other things, in a country that wasn’t at all convinced it wanted such a costly and disruptive production in the first place. It was a patently unachievable ambition, and for the next several months they patently failed to achieve it. In an open competition, 245 designs for the exhibition hall were submitted. All were rejected as unworkable. …

“Into this unfolding crisis stepped the calm figure of Joseph Paxton, head gardener of Chatsworth House, principal seat of the Duke of Devonshire. … When he learned that the commissioners of the Great Exhibition were struggling to find a design for their hall, it occurred to him that something like his [garden] hothouses might work. While chairing a meeting of a committee of the Midland Railway, he doodled a rough design on a piece of blotting paper and had completed drawings ready for review in two weeks. … The architectural consultants pointed out, not unreasonably, that Paxton was not a trained architect and had never attempted anything on this scale before, But then, of course, no one had. …

“The risks were considerable and keenly felt, yet after only a few days of fretful hesitation the commissioners approved Paxton’s plan. Nothing - really, absolutely nothing - says more about Victorian Britain and its capacity for brilliance than that the century’s most daring and iconic building was entrusted to a gardener. Paxton’s Crystal Palace required no bricks at all - indeed, no mortar, no cement, no foundations. It was just bolted together and sat on the ground like a tent, This was not merely an ingenious solution to a monumental challenge but also a radical departure from anything that had ever been tried before.

“The central virtue of Paxton’s airy palace was that it could be pre-fabricated from standard parts. At its heart was a single component - a vast iron truss three feet wide and twenty-three feet, three inches long - which could be fitted together with matching trusses to make a frame in which to hang the building’s glass - nearly a million square feet of it, or a third of all the glass normally produced in Britain in a year. A special mobile platform was designed that moved along the roof supports, enabling workmen to install eighteen thousand panes of glass a week - a rate of productivity that was, and is, a wonder of efficiency. … In every sense the project was a marvel. …

“The finished building was precisely 1,851 feet long (in celebration of the year), 408 feet across, and almost 110 feet high along its central spine - spacious enough to enclose a much admired avenue of elms that would otherwise have had to be felled. Because of its size, the structure required a lot of inputs - 293,655 panes of glass, 33,000 iron trusses, and tens of thousands of feet of wooden flooring - yet thanks to Paxton’s methods, the final cost came in at an exceedingly agreeable 80,000 British pounds. From start to finish, the work took just under thirty-five weeks.

St. Paul’s Cathedral had taken thirty-five years.”

Destruction.

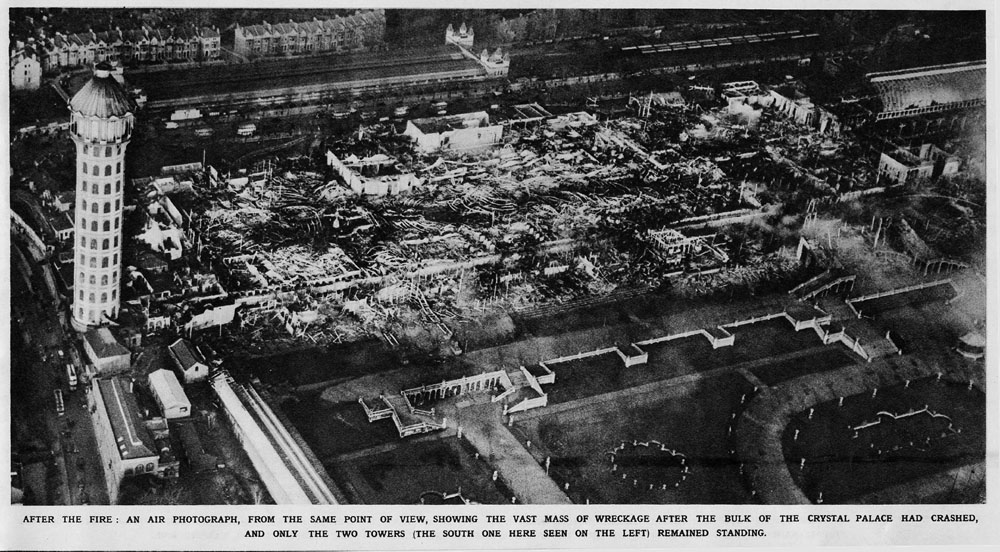

(From Wikipedia) On 30 November 1936 came the final catastrophe - fire. Within hours the Palace was destroyed: the glow was visible across eight counties. That night, Buckland was walking his dog near the palace, with his daughter (Chrystal Buckland, named for the palace) when they noticed a red glow within. Inside, he found two of his employees fighting a small office fire, that had started in the women’s cloakroom. Realising that it was a serious fire, they called the Penge fire brigade. But, even though 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen arrived they were unable to extinguish it. (The fire spread quickly in the high winds that night, because it could consume the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building.) Buckland said, “In a few hours we have seen the end of the Crystal Palace. Yet it will live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world”. 100,000 people came to Sydenham Hill to watch the blaze, among them Winston Churchill, who said, ”This is the end of an age“.

It’s also worth just scrolling through a Google image search to get an idea of the immense size of the thing.

effectiveblu-blog liked this

effectiveblu-blog liked this aliceobsidian-blog liked this

andidigress reblogged this from chazhuttonsfsm

periferiadomestica liked this

andidigress liked this

ronisolomondds liked this

ronisolomondds liked this nachodaveproxy liked this

entangledspaces liked this

529 liked this

nytbutterfly reblogged this from chazhuttonsfsm

joyfooltotheworld-blog liked this

ikebaha liked this

ikebaha liked this vermaphrodite reblogged this from chazhuttonsfsm

chazhuttonsfsm posted this