Idea to Market in 5 Months: Making the Glif

On July 11th, 2010, Tom Gerhardt and I had an idea for an iPhone accessory: a tripod mount that doubled as a stand. Five months later, customers began to receive our product, the Glif, in the mail. This turnaround, from idea to market in five months by two guys with no retail or manufacturing experience, signifies a shift in the way products are made and sold – a shift only made possible in the last couple years.

The best compliment anyone could give us about the Glif project is that it inspired them to take their creative idea to fruition. The purpose of this piece is two-fold: to give an inside look at our creative process, and to offer guidance and inspiration for those who have their own ideas they’d like to see brought to reality.

Design

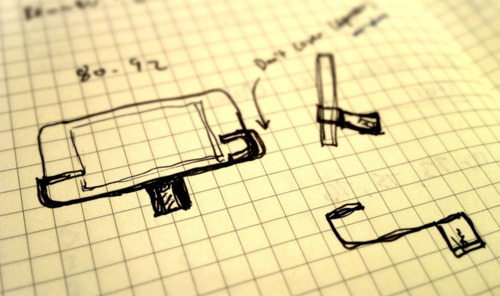

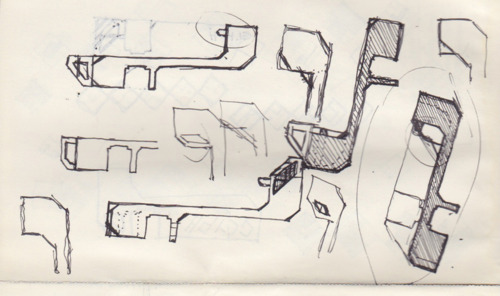

Although neither Tom nor I have a background in industrial design, our education in design and the iterative design process served us sufficiently throughout the project. Like all projects, it began with the kernel of an idea, and our excitement for the idea led us to begin sketching immediately.

From the beginning, it was clear that simplicity was going to be a key tenet of our design. Not just for philosophical reasons, but to keep the design focused, and quite frankly, achievable. We knew that any complication to the manufacturing (moving parts, assembly, etc.) would make the project less likely to succeed.

After a round of sketching, we arrived at the general shape rather quickly: something that affixes to the corner of the phone and runs along the long edge, with a tripod screw roughly centered on that edge. One key component of our early design was a small peg located inside the shoe of the Glif, meant to be inserted into the headphone jack for extra stability. We were both in love with this feature, but in an example of killing your darlings, realized the design was better served (and more versatile) without it.

From our sketches, Tom created a 3D model in a piece of software called Rhinoceros. This software is generally expensive, but currently free for Mac as a beta trial. Seeing our design in 3D was certainly a step up from the sketches, but nothing would compare to actually holding something physical in our hands. Fortunately for us (and the indie product design world at large), this is now not only possible, but fast and affordable.

Shapeways is an on-demand 3D printing company based in the Netherlands (and soon New York). On their website, you can submit 3D models of your design (created in heavy duty software like Rhino or something as simple as Google Sketchup), select the material, and in about 5-10 business days have a physical, 3D printed realization of your model. 3D printing is an additive process, so it is possible to get some pretty crazy designs, and in some cases designs that would be basically impossible to manufacture any other way.

The huge advantage of 3D printing is that it is now cost effective to have a quantity of one manufactured. This makes it an ideal technology for quickly prototyping ideas, especially in regards to testing the object’s form factor.

Upon receiving our first prototype in the mail, we could immediately see that our idea of how the stand would function was flawed. There was basically no way for us to have known that without having a physical prototype to test. It became much easier to iterate once we began receiving prints from Shapeways. Due to the 10 day turnaround Shapeways required, we would begin working on the next iteration while the previous one was being manufactured.

After about 10 iterations, we arrived at a prototype that we were fully satisfied with. Now, the question: how the hell are we actually going to make this thing?

Promotion

Tom and I spoke extensively about how we wanted to sell the Glif. We could do a limited edition run of 3D prints, to gauge interest. We could borrow money or seek investors to fund the initial injection molding run. We finally landed on Kickstarter, a brilliant website for crowd-funding creative projects. My first blush with Kickstarter was when I helped fund the ’Designing Obama’ book by Scott Thomas. The conceit almost seemed too good to be true at the time (“I get to help fund this project, AND I get the book at the end?”) Tom and I realized that Kickstarter was going to be the way to go. It minimized risk, as well as helped create a personal connection with the customers – something very important to us. Because of the way we were going about this project, it made no sense to act like a faceless corporation. We wanted honesty to be reflected in our approach.

We began a dialog with Kickstarter (a new project must go through a brief approval process) and realized the promotional video was going to be a key component to our campaign. Fortunately, Tom and I both have video experience. I had actually considered (and applied) to film schools before making the wise decision to pursue design. We had an immediate vision that the ’Judy is a Punk’ montage in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums was a fine template for the piece. As a little Easter egg for the hardcore Apple fans, I asked Adam Lisagor to star in the FaceTime scene, and he graciously accepted.

Speaking to the camera (at the beginning and end of the promotional video) was actually the hardest part, owed to the fact that neither Tom nor I are trained actors. It is incredibly difficult to sound natural. My best advice: do lots of takes. And take a couple whiskey shots.

Aside from the video, there are some other key components to a Kickstarter campaign that are imperative to the success of the project. Craig Mod’s beautiful write up on his own successful Kickstarter project was invaluable to us, especially regarding strategy behind pricing tiers. It’s a must read for anyone looking to fund a project on Kickstarter.

If there was one mistake we made in setting up the pricing tiers, it was attempting to embed different shipping costs (for domestic, Canadian, and international) within the tiers. This ended up confusing quite a few people, and we did a poor job communicating how this was meant to work. Best advice: however simple you think your pricing tiers are, make them even simpler.

One of the most valuable (and humorous) classes I took while in grad school at Parsons was called ‘Internet Famous.’ It was taught by Jamie Wilkenson, James Powderly, and Even Roth, no strangers to the Internet fame game. The goal of the class was simple: to try to get noticed on the Internet. As silly and narcissistic as that sounds, it provided an invaluable exercise in attempting to understand what makes the web tick, and more specifically, how to get traffic. The key take-away I got out of this class is to be proactive. The bloggers will rarely come to you; it is your task to make their job easier by seeking them out and providing the pertinent information.

If you are looking to promote your project, it mostly likely falls into a niche category that is covered by an influential blogger. Seek them out.

Our niche could be described as 'designy-early-adopter-Apple-fans,’ which incidentally falls right into John Gruber’s wheelhouse. I had the fortune of having a modest rapport with Mr. Gruber, as he has linked to this blog a few times in the past. Needless to say, our Kickstarter page experienced a dramatic 'Gruber Bump.’ To wit, we reached our initial $10,000 funding goal 1 hour and 25 minutes after the post went live on Daring Fireball. And it didn’t stop there.

Follow up traffic from CNET and Gizmodo created a surge in the second day. After the first 5 days things leveled out, but maintained fairly steady gains throughout the duration of the project, with a slight blip on the last day.

After getting some analytics back from Kickstarter, we were able to analyze the most effective publicity we received. The top 15 are listed below. The figure to the right of each listing is the site’s ‘value,’ which we established by multiplying the number of visits by the conversion rate (those that committed to a pledge).

- Direct (Kickstarter.com) - 58,130 x 2.74% = 1,594.8

- theglif.com - 20,893 x 6.67% = 1,398.4

- Kickstarter Newsletter - 7,440 x 6.63% = 493.4

- Google (Search) - 12,395 x 3.50% = 434.2

- Facebook - 6,651 x 5.28% = 351.3

- Daring Fireball - 7,369 x 4.66% = 343.4

- Google (Referral) - 5,025 x 4.95% = 248.7

- TUAW - 5,044 x 3.68% = 185.5

- Twitter - 5,814 x 2.78% = 161.8

- Economist.com - 3,398 x 3.37% = 114.5

- Gizmodo - 2,013 x 4.90% = 98.7

- Boing Boing - 2,360 x 1.84% = 43.4

- Mashable - 864 x 5.02% = 43.4

- iphoneislam.com - 2127 x 1.86% = 39.5

- ipodtouchlab.com - 469 x 8.40% = 39.4

Some press (including CNET) primarily linked to theglif.com instead of our Kickstarter project page, hence the inflated figure. Perhaps most interesting (to us at least) is how high Facebook placed, even though we made virtually no effort to publicize there (electing instead for Twitter). That Zuckerberg character must be on to something.

Another surprising trend we noticed is how many international backers we had. I had originally guessed it would be about 5-10% of our total contributors, but it ended up accounting for over 30%. Once we opened the online store at theglif.com, that figure climbed to over 50%. I suppose it’s not surprising; the iPhone is available worldwide and the Internet knows no boundaries.

Obviously, we were blown away by the response our project received. We had about a 24 hour visit to cloud nine before we got down to brass tacks. The project had blown up to a scale we weren’t expecting, and a whole new series of challenges were present. A good problem to have.

Reality

Finding a manufacturer was our first order of business. When we imagined the scale being much smaller, we had planned on using ProtoMold for the injection molding, and we would melt the brass tripod inserts into the Glif manually. This was thrown out the window after the first day of funding, when the scale became too large to reasonably still expect to do that.

We found some companies through Google searches; others contacted us directly after hearing about our project and knew we were looking for a manufacturer. We ended up speaking with and getting quotes from six companies. All but one worked out of the US but maintained the actual manufacturing facilities in China. That 'one’ is the company we ultimately picked.

Premier Source is a division of Falcon Plastics, both of which are located in Brookings, South Dakota. We chose them for a few reasons. From the onset, they just 'got’ the project. It was very easy to communicate our goals and objectives when they already had a very good idea of what we were trying to create. It was also important to us that their facilities were located in the United States. Visiting the facility was an amazing experience, and allowed us to fully understand how our project was being created. That’s not to say we couldn’t have visited a facility overseas, but it certainly would have complicated things.

We sent a 3D model of the Glif to Premier Source, and Joel (the engineer who worked on our project) began creating a model of how the mold itself would be designed. Once approved, they ordered the steel and machined it using a variety of processes, including one called Electrical Discharge Machining.

After the steel mold was made, it was time for Tom and I to head down to South Dakota for final sample approval of the Glif. We spent a few days on the factory floor, working directly with the engineers at Premier Source, tweaking variables in the injection molding process to get everything just right. We then decided on a few quality control standards, and let the machine run.

The next big problem to solve was order fulfillment. We could handle the ~500 orders of 3D prints, but there was no way we could efficiently ship out over 5000 orders. Enter Shipwire.com. Shipwire stores your inventory in several possible warehouse locations, and will take care of fulfilling your orders. It’s costly, relatively speaking (now I know what the 'handling’ part of 'shipping & handling’ is for) but completely worth it. The great thing about Shipwire is they tie directly to the online store we built (using Shopify), so orders are sent from the store to the warehouse, seamlessly. When Shipwire first received our inventory from the manufacturers, they shipped out over 7000 orders (all of Kickstarter plus some online orders) within 24 hours. Awesome. (Update: We have been working closely with Shipwire since the time of this writing and they have been really great about getting shipping prices as low as possible. If you are looking for an order fulfillment service it behooves you to check them out).

The last touch was to create a bit of packaging for the Glif. We wanted it to be simple (unsurprisingly) and include instructions for using the Glif. We also knew that it didn’t need to be retail friendly just yet (we could cross that bridge later) so there was no need for gratuitous plastic or excessive packaging. In the end, it became a simple die-cut craftboard card, printed on both sides with black ink. The shape of the Glif allowed it to stay in the card without any additional adhesive or attachments.

For all the hard work that this project required, the positive feedback we have received has made it more than worth it. People seem to be loving their Glifs, and it’s an awesome feeling. One thing that has greatly pleased Tom and I about the the success of this project is its inherent simplicity: we are just two guys who made something people want to buy, and then we sell it to them. No middle men, no big corporations, no venture capital, no investments. I think beyond the interest in the Glif itself, people like to know where things are coming from, and the story behind it. So thanks for letting us tell our story.

Admittedly, it took quite a bit of good fortune and luck to pull off the success we had with the Glif, but I hope this piece can serve as a template for any inventors or entrepreneurs out there. The world is changing in a pretty incredible way, driving the financial risk for a project like the Glif basically down to zero. There is no excuse to not get your idea out there and see what happens. You never know.

We want to send a heartfelt thanks to everyone who made the Glif possible: all of our wonderful Kickstarter backers, of course; Kickstarter itself for having a great service and being very helpful every step of the way; Mr. Gruber for getting the ball rolling; Patrick Buckley of Dodocase for giving us some invaluable advice and recommendations; Premier Source for doing an amazing job with the manufacturing, and Shipwire for doing a great job shipping all these orders out. We couldn’t have done it without you.

Breakdown:

3D modeling software: Rhinoceros for Mac

3D printed prototypes: Shapeways

Project funding: Kickstarter

Manufacturing: Premier Source

Printer (for packaging): Keystone Folding Box Co

Fulfillment Service: Shipwire

eCommerce Store: Shopify

Domain Hosting: Dreamhost

Payment gateways: Braintree and Paypal

Email campaigns: Mailchimp

Monitoring Internet chatter: Google Alerts

Monitoring Twitter chatter: Tweet Deck for iPhone

January 17, 2011 / 1,375 notes

itsalfredokaramlove-blog liked this

itsalfredokaramlove-blog liked this dualsrecords reblogged this from russianpencil-blog

dualsrecords liked this

ghostxhearts reblogged this from russianpencil-blog

ghostxhearts liked this

wariorojas reblogged this from russianpencil-blog

b-e-s-o-costardiamant liked this

ease-hike-trim liked this

laughingwiththestorm reblogged this from russianpencil-blog

laughingwiththestorm reblogged this from russianpencil-blog tomorrowstea liked this

courtneybrownmakesprints-blog liked this

seanrainey-blog liked this

i-zygzak-blog liked this

zhengger liked this

zhengger liked this punchdrunkpanda-blog liked this

gifts-for--men liked this

gifts-for--men liked this camere-de-supraveghere-blog liked this

russianpencil-blog posted this

- Show more notes