Drought is arguably the biggest single threat from climate change. Its impacts are global. Some say drought triggered the crisis in Syria that sent tens of thousands of refugees heading for Europe this summer. Relief failures and poor drought forecasting caused innumerable deaths in the Horn of Africa during 2011 and 2012. Yet calls to head off future disasters by establishing a UN body to provide a global drought early warning system, first made almost a decade ago, remain unfulfilled.

A drought can be defined in various ways. A meteorological drought, for example, is when the rains fail. A hydrological drought is when the lack of rainfall goes on long enough to empty rivers and lower water tables. Agricultural drought begins when the lack of water starts killing crops and livestock. And after that, people may start dying too.

Right now, international agencies defer to national governments before declaring a drought, because they say it is partly subjective, and highly political. Nobody is accepting responsibility for setting up a global body, and nobody is putting up the necessary funding, say experts in the field. The UN climate event in New York last month passed without any further progress.

To further complicate matters, current forecast mechanisms, which require good forecast data and local knowledge to see how dry conditions will impact local water and food supplies, are unreliable and are least likely to be acted on to prevent disaster in the countries that are most at risk.

Droughts, however you define them, can’t be prevented. All the technical gizmos in the world haven’t stopped wells emptying in California after four years of low rains. But with research and collaboration, a global early warning system can stop failed rains resulting in empty grain stores, and refugee camps full of hungry people in vulnerable parts of the world. Meteorologists and aid professionals say a global agency could fill the gaps and save millions of lives.

Calls for an international monitor

A global system that would monitor upcoming droughts and issue warnings was first proposed at a ministerial summit in South Africa in 2007 by US government researchers, headed by Jay Lawrimore of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Initially, the UN’s world climate research programme took up the challenge. A workshop in Barcelona in 2011 called for the creation of a global drought information system. But, despite some early cash from the European Union, funding never came through, says meteorologist Will Pozzi of the Vienna Institute of Technology, an early advocate.

The project has stalled because no existing agency has accepted responsibility. Neither the weather watchers at the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), nor the guardians of food supplies at the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) have taken on the idea.

The UN Convention to Combat Desertification, which meets in Ankara next month, “would be a natural ally,” says Pozzi. “But their main focus is on policy.” It has little interest in doing the science to make an early warning system work, or to galvanise the real-time planning that could prevent drought turning to disaster.

Difficulties of drought response

Responding to droughts is not an easy task. For one thing, forecasting needs to be improved. Without better forecasting, more early warnings could prove worse than useless. Studies looking back over the past three decades found that only around a quarter of droughts were successfully forecast a month or more ahead – and almost as many warnings turned out to be false alarms, says Pozzi. The poor rains in east Africa in late 2010 were successfully predicted, but the failure of the longer rainy season the following spring, which turned crisis into disaster, was not predicted. But more research could improve that.

A new body could also improve the yawning gaps between meteorology and hydrology, and between hydrology and humanitarian need. The links are complex. In some places and times, lack of rain is compensated by access to underground water, manmade reservoirs or moisture stored in soils across forested watersheds. Elsewhere, without such buffers, drought rapidly escalates into shrivelled crops, dead livestock loss and, if the people are poor and unprotected, hunger and death. Distinguishing between the two scenarios is as vital as predicting the rains.

But there is a third element. No amount of early warning will work without action to protect the most vulnerable, says Roger Pulwarty, a drought specialist at NOAA. Pulwarty believes past food crises show that “agencies respond late for the most part, delivering fodder when pastures were recovering or distributing seeds after rains have passed”.

Conflict or cooperation?

Not everyone is convinced that a new body in New York or Geneva is a good fit for this complex set of problems. “The idea of a big international drought agency is a false objective. I prefer a bottom up approach,” says Robert Stefanski, who runs the WMO’s agricultural meteorology programme.

Part of his reasoning is political. A new drought body could create conflict rather than cooperation. Many governments think that, like famines, droughts bring shame on their countries. “Declaring a drought is a sensitive thing,” says Stefanski. “We at WMO cannot declare a drought, all we can do is announce when a government agency within the country does so.”

But those in favour of a global agency think that it would prevent institutional denial, galvanise governments and bring global expertise to protect victims.

It would also be a recognition that local droughts have global impacts. Some researchers have argued that drought in Syria triggered the internal migrations that destabilised the country, leading to civil war, the rise of Islamic State and a mass exodus from the country.

And when failed rains destroy export crops, it can send shock waves round the world. Years of drought decimated grain harvests in Australia and sent global grain prices soaring in 2007 and 2008 – triggering bread riots and political chaos from Haiti to north Africa.

“In an interconnected world, the need for information on a global scale is crucial for understanding the prospect of declines in agricultural productivity and food prices, food security and potential civil conflict,” a consortium of 27 drought scientists, headed by Pozzi, wrote in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society two years ago, while calling for a global early warning system.

Drought trends for the future

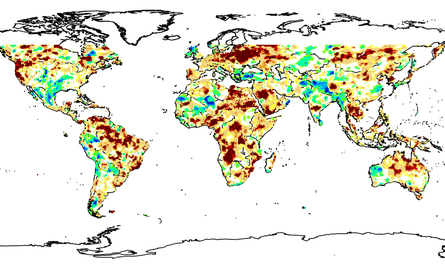

The future of droughts as climate change takes hold remains uncertain. Even present trends are unclear. In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that “droughts have become more common since the 1970s”. But it has since backtracked because of doubts over the reliability of the Palmer Drought Severity Index, a widely used measure that calculates the difference between rainfall and evaporation.

The latest IPCC assessment, published last year, found some signs of more droughts but concluded that “there is not enough evidence at present to suggest more than low confidence in a global-scale observed trend in drought ... since the middle of the 20th century”.

Whatever the trends, the complex issues surrounding drought require the world’s attention. Drought, as Pulwarty puts it, “is among the most damaging and least understood of natural hazards”. Places such as western and southern Africa, and parts of India and South America “face recurring severe droughts [but] still do not have comprehensive information and early warning systems in place”.

“Let’s not imagine that someone sitting in a laboratory or an office at the UN can solve the drought issue,” says Stefanski. But let’s not ignore their expertise either. The task is urgent, whether taken up by a new UN agency or a souped-up network of drought scientists. It is important to combine better meteorological forecasts with detailed knowledge on how landscapes and societies respond to a dearth of rain – and to turn that knowledge into prompt action within weeks, sometimes within days.

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow @GuardianGDP on Twitter, and have your say on issues around water in development using #H2Oideas.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion