5 Lessons From Longshot, a Magazine Made in 48 Hours

Weekends bring out the avocation in people. Some rock-climb. Other people play in basketball leagues. Hobbyists build robots. My friends and I make magazines.

I co-founded Longshot Magazine with Mat Honan and Sarah Rich a few months ago. Our mission: to occasionally come together to write, edit, design, and ship a magazine in 48 hours. We accept contributions from all over the world and do it all with basically no money. It's sort of insane, but also tremendously fun and a great way to learn new skills. (We don't really make any money from it, but that's also completely beside the point.)

Everything we do is made possible by the new (free) technological tools out there. But we're the ones that have to figure out how to deploy -- in what constellations, in what order -- to actually run a magazine. Steel, engines, an assembly line, and some workers don't just make cars on their own; you have to figure out how it works.

Lesson 1: Magcloud makes it possible.

Magcloud is a print-on-demand service run by HP. They allow you to put out a 60-page glossy, perfect-bound magazine for about $10 (if you give them an ad on the backpage, etc). What they allow you to do is start a magazine without the money you'd need to actually print the thing. (More on the economics of it later).

Lesson 2: Twitter makes it work.

Twitter is the social ligature of our project, and (I would say) of creatives more generally. We pretty much only get the word out about Longshot through Twitter and an email list. Yet thousands of people have sent in submissions and more than a hundred have dedicated serious amounts of time to the production of the magazine.

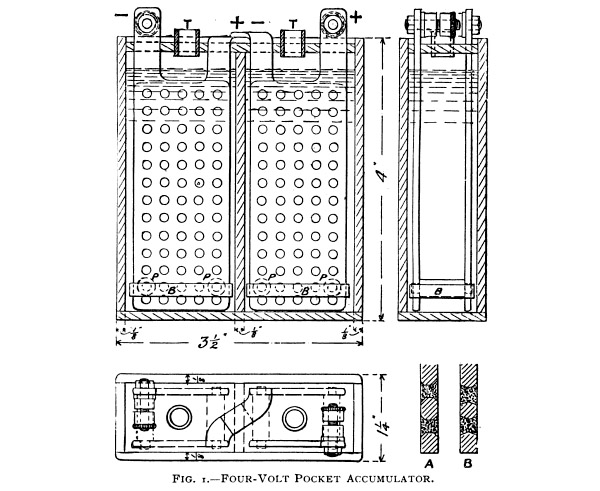

The thing about Twitter is that it's interest-based, but the cost of following someone is low, so you tend to branch out beyond your tight work circle and your friend network. The end result is that these sparse networks grow and mature. One thing they lack is a focal point. I think Longshot (and other meatspace and/or short term events) distill these diffuse groups. Perhaps a better metaphor is that it allows us to conduct some of the electric serendipity of Twitter into a specific vessel. In the early days of batteries, they were called, "accumulators." Maybe Longshot is an accumulator for Twitter. (Or even a pocket accumulator, see below.)

Lesson 3: Workflow matters more than tools, but the tools help define your workflow.

After we've gotten the word out, and people start sending things in, the biggest challenge is managing all the photos, illustrations, and text coming in. Last time, we had a homebuilt reviewing system that did the job, but was still in pretty rough shape. This time we used Submishmash, an off-the-shelf tool, and it blew our minds. All of our submissions flowed through that tool. We could assign them to people for review and editing.

That said, it was having Erik Malinowski, a longtime Wired affiliate and lead blogger for the Playbook blog, acting as our managing editor that really made this issue much smoother. He took charge of assigning things and just making sure that Sarah, Mat, and I didn't do anything stupid (too often).

Our workflow was light years ahead of last time, but was far from perfect. You can't edit documents in Submishmash, so that required using an outside system. From there, all of the actual editorial work took place on Google Docs, which proved remarkably resilient. We had folders set up and as we pushed things forward, they got moved from 01 (selected by triage editors for further reading) to 02 (edited once) to 03 (selected for the magazine, edited, and ready for pick-up by design).

As you might expect, our biggest mistakes came from the breakdowns in communication between the Submishmash system and Google Docs. If there were a way to link the two, it'd be a dynamite, high-speed, media-making engine. (Update: Yes! In the comments, Mike Fitzgerald of Submishmash says, "We've completed a Google Docs prototype and plan on release sometime near the end of this month.")

Meanwhile, the designers, led by the incredibly talented Keith Scharwath, were figuring out where everything was going to go and getting things set up. Almost all of our interactions with them were face-to-face because that's just what worked. It would have been impossible to do what we did without working in the same room.

Particularly because at the end of the process, copy editors scrubbed the text on printed out pages.

We kept a Ustream livefeed of the production areas going for most of the weekend, but to be honest, it was pretty boring. People making magazines are having fun and occasionally doing strange things like taking pictures of dogs with hats on, but most of the time they are staring at computers or printed pages. Every feed watcher said, "You guys are so quiet."

That's because there is a limitation to the event-as-media model. Mediamaking requires conscious dedication to something that only exists on a page. We're not dancing. We're not singing. We're writing and reading and, even communally, that's a private experience.

For what it's worth, I think our Twitter feed worked better, perhaps because it's also a collective reading experience.

Next time, I'm not sure how much we'll stream from the process. My vote would be, "not much." And not just because Gary Shteyngart convinced me streams are almost the opposite of art.

Lesson 5: If people matter, media isn't dying.

I spent 48 straight hours with a crew that ranged upwards of 50 people and included contributions from dozens more. Every single one of us cared deeply about the design and content of words on pages. We love making media and whether it's print or digital, it's just what we do and we'll continue doing it.

At a time when there is so much doom and gloom about the industry, I see Longshot as a kind of backstop for us. If the economics of our industry continue to fall apart and we all end up working in advertising, we could still do Longshot as often as we all wanted to. It doesn't cost anything but some blood and sweat. And it does something good for that part of us that got into media because we wanted to engage people with the truths of the world.

That's a drive that predates the Internet and that will happily live through and with it.