Is multi-tasking a myth?

- Published

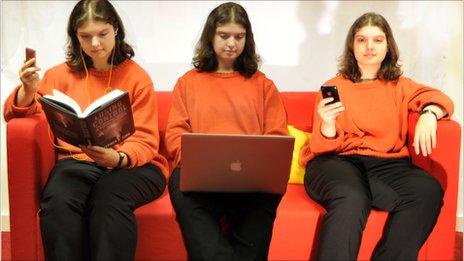

Britons are increasingly overlapping their media habits - tapping out e-mails while watching TV, reading a paper while answering texts from friends. But, asks Hugh Wilson, does media multi-tasking mean instead of doing a few things well, we are just doing more things badly?

I was watching a documentary the other day about an educational issue that - as the father of a child about to start his first year at school - held more than a passing interest.

At the same time, I was actively participating in a three-way text message conversation about the coming weekend.

It's fair to say that, by the end of the evening, I had only a vague understanding of the message of the documentary and the weekend remained largely unplanned. I had multi tasked, but I hadn't done it particularly well.

Still, I was only doing what comes naturally, at least if the latest report from media regulator Ofcom is to be believed.

According to the Ofcom analysis, the average Briton spends seven hours a day watching or using media. But that figure rises to nearly nine hours when you squeeze in time many of us now spend using several devices at once.

So we watch telly while surfing the net, or continually check Facebook updates while writing a report, or send instant messages while talking on a mobile phone.

Of course, people have been reading while listening to the radio for years, but the increase in multi-tasking seems to be different. Philosopher Damon Young, author of Distraction, says that we've become habituated to checking e-mails and texts, and turn towards the "safe novelty" of Facebook rather than the important but tricky stuff of real life.

"And it's often required by employers, or work culture," he adds. "Good employees must be 'available'… (even) after hours and on weekends."

Indeed, media multi-tasking sounds, at first glance, like a boon for productivity. If we can do two things at once, we can do twice the amount in the same length of time, or the same amount in half the time. Either way, it's a nifty trick.

But it's not quite as simple as that, as my frustrating evening demonstrated. A raft of studies has found that, actually, multi-tasking is a good way to do several things badly.

For example, studies by Gloria Mark, professor of informatics at the University of California, have found that when people are continually distracted from one task, they work faster but produce less.

Another found that students solving a maths puzzle took 40% longer - and suffered more stress - when they were made to multi-task.

Clumsy switching

And researchers at Stanford University found that regular multi-taskers are actually quite bad at it. In a series of tests that required switching attention from one task to another, heavy multi-task had slower response times than those who rarely multi tasked.

What that suggests, the researchers say, is that multi-task are more easily distracted by irrelevant information. The more we multi-task, the less we are able to focus properly on just one thing.

Damon Young thinks where media and communications are concerned, we're not made for multi-tasking.

"When we move from our job to an e-mail, it takes about a minute to recover our train of thought," he says. "And then we get another e-mail, or an SMS, so our concentration is fractured. The result? We're not really multi-tasking. We're switching between tasks in an unfocused or clumsy way."

And unfocused can mean unproductive. US studies have shown that students who do homework while watching television get consistently lower grades.

Yet, in other areas, we seem to be dab hands at multi-tasking. We can walk and talk, after all. And if that sounds a bit simplistic, we can also control a large slab of speeding metal while holding an intelligent conversation with the person in the passenger seat.

Mirror, signal, sing-a-long

Some of this, says Professor John Duncan, a behavioural neuroscientist at Cambridge University, is down to practice. When you're learning to drive, changing gear takes all your focus. When you've been driving for 10 years, you can change gear, check your mirrors and sing along to the radio, all at the same time.

So some familiar tasks are easier to do simultaneously. In that respect, our brains are brilliant parallel processors. But according to Professor Duncan, that's usually the case only if the tasks are sufficiently different.

"There were experiments in the 50s when subjects were played two speech messages at the same time, and were asked to concentrate on one," he says. "It's quite amazing how little they took in from the other one."

Amazing, but as it turns out, quite logical. "The brain has very specialised modules for different tasks, like language processing and spatial recognition. It stands to reason that two similar tasks are much harder to do simultaneously, because they're using similar bits of tissue."

Neuropsychologist Professor Keith Laws says genuine high-level multi-tasking is impossible in humans.

"The general understanding people have of multi-tasking is a bit of a misnomer. I've never seen any examples of anyone who can do three or even two intelligent tasks simultaneously," says Prof Laws.

Which is probably why we seem to have trouble multi-tasking with media. Driving and talking doesn't use the same bits of brain. Answering an e-mail while chatting on the phone does. In effect, we are creating information bottlenecks.

"What we really mean by multi-tasking," says Prof Laws, "is the ability to plan and devise strategies to do all the tasks we have to do and navigate our way through them."

But if consuming a plethora of media at one time is impossible there is evidence some people are better than others at switching between them rapidly.

And there is some truth in the adage that women outperform men in this, says Prof Laws - although the weight of evidence is by no means as strong as many people assume.

Last month he reported back on an experiment which, he claims, provides the first concrete evidence women are better multi-taskers than men. Until then, the belief had been just that - a belief.

"Until now the theory has largely been folklore," he says, "[It's] a bit like the folklore which perpetuates the belief that men are better at concentrating on one task at a time."