The death and rebirth of Hyundai Trajet Y264 TKP

- Published

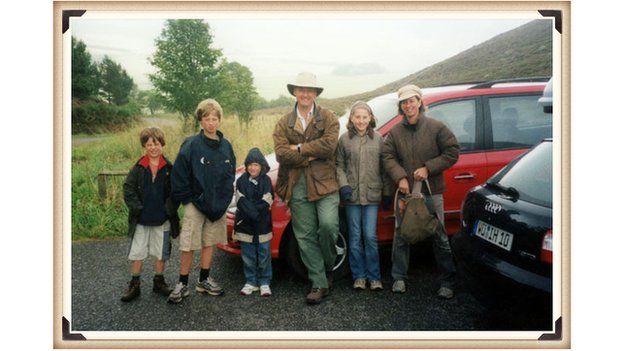

A few miles short of Swindon my car, laden with four teenagers, my wife, one teenager's boyfriend, a dog, and attendant baggage comes to a sudden and it turns out, permanent, halt.

Two days later Hyundai Trajet Y264 TKP is shunted into a Cornish garage, and declared by the owner George to be "finished".

Or in the words of the recycling industry, it has become an end-of-life vehicle.

Here rusty hulks lie forlornly in a line waiting for scrap - after hundreds of thousands of miles of family holidays, car-sick children, back-seat driving, wasp-rich picnics and school runs.

Remembering the car was 12 years old, I chirpily mention that a £150 cheque from a scrap merchant would come in handy.

"£150? Lucky to get £50," says George.

George sits in his office outside the tiny Cornish village of Doublebois and patiently explains the macroeconomic forces at play that have reduced my car to a hunk of worthless metal.

China, he reckons, is the problem. With Chinese demand falling, the price of iron ore is on the way down and scrap metal prices are following in their wake.

A year ago George could have got £160 for my car. During the Beijing Olympics prices skyrocketed.

Not now. "There's a worldwide glut of metal," he explains.

And Y264 TKP is 75% metal, albeit dented and scratched by bike racks, my mother's gate post and, for reasons too complex to go into, the teeth of a small pony.

'Bloody painful'

There are other problems too - the collapse in demand, unsurprisingly, from Ukraine, and the eurozone recession.

One insider put it bluntly: "The business is bloody painful".

Charles Ambrose of the UK's Motor Vehicle Dismantlers' Association (MVDA) said: "In the last few years we've lost 30 members or so going out of business. Most of them are long term players. They are being kicked from all sides."

George will bear away poor crippled Y264 TKP to be eviscerated in an "authorised treatment facility". It will be "de-polluted", the battery, and tyres removed, the diesel, oils, and brake fluids sucked out.

The oils will be re-refined or used as fuel. The battery will be ground down, the acid neutralised, the polymers separated from the lead, to go towards making a new one.

Black market

Of course, I could bypass George altogether and get a little more - cash in hand - from someone, er, less respectable.

The MVDA believes 600,000 of the 1.7 million cars scrapped every year simply fall off the official radar, unregistered, untaxed. The paper trail vanishes into a black hole, or rather a black market.

Environmental niceties are not observed on the black market.

But the expense of putting anything in a landfill in the UK and the difficulty of dumping cars means even the vanished ones work their way back into the recycling system.

"It's hard to know exactly where those cars go," says Mr Ambrose. "We know a tremendous number are broken up and the parts end up on eBay.

"Others are exported as whole cars or as spare parts. Parts of your car could end up in a vehicle in Nigeria. That's not a problem environmentally. It's still recycling.

"But the money involved in this kind of black market is often also involved in crime."

The plastic bits

So one way or another almost 95% of Y264 TKP will be recycled. The UK is expected to hit the 95% car recycling target set by the European Union's end-of-life vehicle directive this year or next.

Which is why the plastic bits of Y264 TKP, like the cup-holders stuffed with my daughters' hair-ties, will not go to landfill.

The legislation has forced industry to come up with recycling solutions - at a cost.

Ian Hetherington, director general of the British Metals Recycling Association says: "The capital expenditure to develop this kind of technology is very high indeed, and it is only profitable when you are producing very high quality plastics at the end of it."

So the American firm MBA Polymers invested $30m (£20m) to develop technology to recycle high grade plastics.

Its joint venture with the UK's European Metal Recycling (EMR) in Worksop recycles 80,000 tonnes of plastic every year. The plastic pellets are then sold to manufacturers.

The alarming truth is the plastic trim of Y264 TKP, which the dog did such appalling things to on the way home from Scotland in 2008, could end up as part of a Nespresso coffee machine.

Hammel's footage shows the Red Giant car crusher in action

Squeezed margins

But plastic, like metal, is subject to market prices. It is the low oil price this time. Cheap oil makes "virgin" plastic cheaper, so while the law insists on recycling, the margins for the recycled stuff are squeezed.

Then there is the fluff - the padding, the upholstery, and probably the shoe my son lost in 2007. Technically it is ASR, or automobile shredder residue. There is a good chance it will go to landfill.

But there is also a chance it may go through another innovation - a new energy-from-waste plant in Oldbury, in the West Midlands where Chinook Sciences and EMR will turn it into electricity to be sold into the grid.

The grubby left over bits of Y264 TKP will then power, say, my washing machine.

Finally there's the metal - the easy bit, even if its value is small.

Urban mining

Y264 TKP, replete with my memories, will go into a crusher, something like the Red Giant made by the German firm Hammel, or perhaps even the monstrous Hammel 1500DK that will devour a car body in around 20 seconds.

The parts are then separated, using magnets and flotation tanks to divide materials according to their atomic weights.

This is the law of the scrap dealer: Separation creates value.

There are precious metals to be had: rhodium, palladium and platinum, and rare earth metals, once discarded, now picked clean from mirrors, batteries and catalytic converters.

Some call it "Urban Mining".

One recycling expert described it thus: "The iron ore miners take the stuff from below the ground, we just take it from above the ground."

The steel will probably go abroad for smelting. Scrap is best suited for electric arc-furnaces rather than blast furnaces, and the most convenient ones are in southern Europe. Turkey is the favoured destination.

From there, the metamorphosed chassis of Y264 TKP, possibly still tainted with the last few grains of sand from a Norfolk beach holiday, is likely to end up as a small (but I like to think important) part of the frame of a middle eastern skyscraper.

Ian Hetherington adds a final suggestion: "It may though actually go back to South Korea.

"It could even turn into another Hyundai."

- Published16 January 2015

- Published6 January 2015

- Published3 December 2012