Kit Wright’s work is a bracing reminder that rhythm is a limitless resource of language, and that poetry need not sacrifice verbal subtleties to raise its voice in song. Speakable and readable, his new collection ranges from the manic mock heroics of the title poem, Ode to Didcot Power Station, to the descriptive intimacies of the sequence Talking to the Weeds. Not by any means a routinely formal poet, Wright typically invents his own brand of rhythmic repetition, drawing out chimes and patterns as a source of comic intensification. This week’s poem, Lament for Stinie Morrison, is tragedy rather than comedy, deploying a semi-cumulative form, faintly reminiscent of The House that Jack Built, to build up a blaze of outrage and regret.

Stinie (sometimes Steinie) Morrison, originally Alexander Petropavloff, was a Russian-Jewish, East End immigrant and a convicted burglar. In 1911 he was found guilty, on thinly circumstantial evidence, of the murder of an unpopular local landlord, Leon Beron. His death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by Winston Churchill, the home secretary, and he died in Parkhurst prison in 1921 from the effects of a repeated hunger strike, having long given up hope of a retrial.

Stinie lives in this poem. He lives in the refrain, woven round his name, and he lives in the brilliant patchwork of “evidence” gathered from his life and times. There’s no direct portrayal, and yet he’s present – a sinewy, shadowy figure twisting his doomed way through the Whitechapel rat-runs. The poem’s narrative, bold and simple like its dactylic rhythms, reminds us of the essentialist nature of poetry, and the force of its economies.

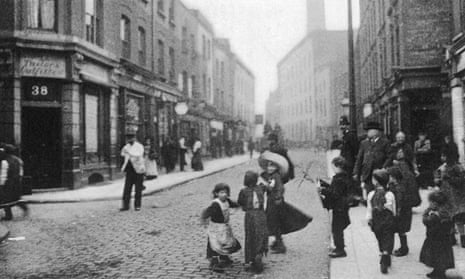

It begins with a drum roll of insistent end-rhymes to summon and compress a vast, unspoken experience, the stony arc that stretches from Petropavloff to “Stinie”, “the canyons of Ukraine” to Whitechapel’s “sharp and hungry streets”. The images in the poem, reinforced by the insistent placing gesture of the demonstrative, are as resonant in their way as the rhythms. “Canyons,” for example, suggests more than geology: the trochee that’s nearly a spondee seems to contain every sort of abyss from which an immigrant might long to escape.

End-rhyme is abandoned after stanza two without loss of power. Like the penny gaff mentioned in stanza three, the poem unfolds a series of vividly shaped, separate but linked dramatic “scenes”. The simile of the streets as tightened fiddle strings, like a clue in a whodunnit, foreshadows the grisly facial wounds received by the victim, cuts resembling the s-marks on a violin. We’re reminded that Stinie himself is a fiddler, in the non-musical sense, but the refrain line’s single amphibrach, part sob, part accusation, constantly reasserts his entrapment and inescapable pathos. There’s pleasure to be had, though, from the local colour, and in the sound effects added by some wonderfully alliterative, Babel-conjuring word play in the fourth verse. The poem is a cross-section through Stinie’s Whitchapel, a district both sordid and culturally dynamic, with Yiddish plays and “bouncing brothels”, fiddle tunes and poems, cockroaches and crime, pressed close in its archaeology.

The narrative crunch comes in stanza five, its delay expertly timed: “This is the man they smashed to death.” Note – “the man”, not the body. Although Beron isn’t named, it’s the killer(s) who are dehumanised in an impersonal “they”.

There are no heroic villains in Stinie’s story, and none of the mythologising of the broadside ballads. The Lament, in its fundamental realism, never loses sight of the social underpinnings of the individual’s tragedy, his lack of choice, and the criminal injustice of his sentence. In the phrase “smack in the frame”, Stinie crumples, as if he’d received from the law no less a bludgeoning than the victim had from the killers. The so-called evidence against him is laid out, but the “guilty” verdict overturned in the synecdoche of the brutally simple, humanly astute summing-up: “and this is Whitechapel and it’s done/ for Stinie”.

Lament for Stinie Morrison (convicted 1911)

These are the canyons of Ukraine

from which he came

to take the name,

to take the name

of Stinie.

These are the sharp and hungry streets

of black Whitechapel, that pulled as tight

as fiddle-strings round the lying throat

of Stinie.

This is the Yiddish theatre played

by flickering candles, penny gaffs

with songs and poems and fiddle tunes

for Stinie.

These are the spielers and shebeens,

the bouncing brothels, the gambling holes

with rat and cockroach working a living

inside them just

like Stinie.

This is the man they smashed to death

on Clapham Common, his ankles crossed,

with fiddle-holes cut in his shrouded face,

and smack in the frame

was Stinie.

This is the fence and this the gold,

the jemmy, the knife, the Browning gun,

and this is Whitechapel and it’s done

for Stinie.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion