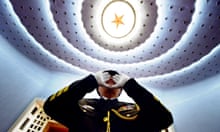

Chinese TV presenter Rui Chenggang has enjoyed a high-profile career, but none of his appearances has drawn as much attention as his absence from screens on Friday.

The unused microphone seen beside his co-anchor on China Central TV's economic news bulletin that night hinted at the suddenness of his departure. Rui was detained shortly before the show, according to Chinese media, becoming the latest high-profile figure to vanish in Xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign.

Leaders have warned for years of a "life and death" struggle for the Communist party. But while previous crackdowns rooted out some high-level names – usually titillating the public with details of mistresses and stacks of cash – they also bred widespread cynicism as brazen abuses continued.

None have pursued the cause for as long or taken it as deep as Xi and his colleagues: witness the defenestration of Xu Caihou, former vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission, and the lengthy investigation into Zhou Yongkang, the former security tsar. Xu is the most prominent military figure to be purged for decades, Zhou is the first former member of the Politburo standing committee (the top political body) to face investigation like this. While Chinese media have not spelt out Zhou's woes explicitly, the hints have grown more blatant by the month, with some identifying him via his family relationships.

Seizing Rui, who built his profile with a nationalist push to remove Starbucks from the Forbidden City, is indicative of the wide-ranging nature of the anti-corruption drive, but is also something of a "sideshow", noted Kerry Brown, whose book The New Emperors focuses on China's top leaders.

Cases that would previously have rocked the media have become simply another announcement in the flood, such as the investigations into Zhang Tianxin, formerly the party boss of Kunming and Wan Qingliang, mayor of Guangzhou.

State media said recently that almost 30 officials of provincial and ministerial level or higher have been investigated for corruption in just over a year and a half, while the total number of cadres punished between January and May was up by a third year-on-year at 63,000.

The lack of interest in Shi Yong's recent trial indicates the scale of corruption that the public have grown used to: the former head of the construction bureau in Jiuyuan, a relatively minor city in Gansu, was handed a suspended death sentence this month for amassing 50m yuan in bribes.

In the past two days alone, Chinese media have reported the expulsion from the party of Hunan official Yang Baohua, for corruption and adultery; the opening of a criminal investigation into three former top officials, two of whom were allies of Zhou; and the death of a Hebei cadre, reportedly killed in a road accident as he fled after learning he was under investigation. Police found 47 bank cards on his body.

"China is certainly taking the anti-corruption campaign very seriously this time – otherwise it would not have taken Xu Caihou," said Wang Yukai, a professor at the Beijing-based Chinese Academy of Governance.

"Not all officials fallen from grace are from the same faction … what matters is not how officials are aligned, but the severity of their corruption."

Yet to Zhang Lifan, an independent Beijing-based historian, the decision to fell so many high-level figures merely reflects the intensity of an internal power struggle.

"If the elimination is not thorough, the whole campaign could lead to a backlash," he said.

Zhang described it as a selective campaign in which the problems of allies were ignored while those in other factions were purged. Ousting Xu and other corrupt officials was also essential to consolidate Xi's control of the military, he argued.

Some of those detained have clear connections with other figures under suspicion, notably Zhou – Ji Wenlin, who reportedly "took a huge amount of bribes and committed adultery", was not only vice-governor of Hainan but a former aide to Zhou. Others are less obvious targets.

That suggests it is not just about in-fighting or a power grab by Xi, suggests Brown. While some see an emerging strongman, Brown believes the system is structured to ensure Xi cannot become a Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping-style figure. "He has to keep people on side, even if we can't see it," he said.

So far, at least, he appears to be successful in doing so. That, to Brown, implies a shared vision to some degree: "You can be very cynical about it, but I think people are fighting for the party they want."

He compares the current campaign to an inquisition and the party to the Catholic church, "with an orthodox doctrine that people have to, at least rhetorically, say they believe in" – a cluster of ideas about the party's intrinsic importance in building a strong and rich China and its moral mandate to lead the country as economic growth slows.

It is not about who is tied to the most money – "there are so many people you could think should be taken" – but about who is judged to be too busy establishing their own kingdoms and using the party's authority purely for their own venal ends.

Some also believe that it is only by clearing out interest groups that China can pursue the economic reforms that it desperately needs, and has promised.

Zhan Jiang, a journalism professor at the Beijing Foreign Studies University and prominent online opinion leader, said officials were now less likely to take obvious bribes and flaunt their power – one sign that the drive should be taken seriously. Even so, people were waiting to see whether or how it developed.

He added: "Mr Xi is currently using his personal power to champion the anti-corruption campaign. The next step, however, should be institutionalising this effort."

That should mean an independent anti-corruption body and the easing of controls over new media, Zhan suggested.

Far from embracing increased accountability or public supervision, authorities have in recent months prosecuted and jailed activists pressing for officials to declare their assets.

"There are anti-corruption campaigns in every dynasty," added Zhang, the historian. "The campaign cannot get rid of the corruption stemming from the very heart of a corrupt system."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion