I used to see a homeless man perched on a curb out the back of Safeway in Camberwell. Although it looked as if he hadn't had a bath or a square meal in a while, I'm ashamed to say the thing that always elicited the most sympathy from me was that he was a passionate reader. His head was always buried in a book. Any book. Horror, science fiction, romance – he was always reading.

Writing while homeless, however, may be tougher to sustain. Doing it at a desk in a warm room can be hard enough: literature is surely the last thing on your mind when you've no food or money.

According to his book, The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp, WH Davies managed it. You'd think that the predicament of homelessness would vary little from epoch to epoch – food and shelter being timeless basic human needs – but The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp, published more than 100 years ago, reminds us that today's homeless have a whole extra set of problems, including the stigma of being one of society's displaced. Davies – a wandering poet who railroaded his way across the US and Canada (where he lost a leg) and tramped around the UK for six years – paints a comparatively upbeat view of an England in which a tramp could depend on food and drink from generous strangers, and in which many doss houses offered bed and board indefinitely. Hardly luxurious, of course – but in Davies' world, the tramp was not the scourge of society but a decent chap down on his luck; a vagabond, rather than a smackhead.

As it happens, though, Davies actually chose to make himself homeless, preferring to pay for the printing of his poems rather than his rent. When you discover that he had access to a minuscule but vital allowance, his plight appears in a slightly different light. The same problem lies at the heart of George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London. The book is a vital piece of socialist journalism, and Orwell undoubtedly got to the heart of what it meant to be destitute. But when the going got exceptionally tough, he had financial benefactors he could call upon, such as his Paris-based aunt, Nellie Limouzin.

All of which poses the question: aside from the poetry pages of The Big Issue, is there such a thing as literature of the homeless? Alexander Masters's heart-breaking Stuart: A Life Backwards illuminated the social problems that lead to homelessness, yet was the product of a Bedales-educated Cambridge graduate. In Hunger, Knut Hamsun created a memorable homeless character who becomes increasingly delirious through starvation but still spends most of his waking moments preoccupied with selling a story to buy a loaf of bread – but he's a fictional creation. For my money, the book that comes closest to authenticating the homeless experience is The Grass Arena, by John Healy, an unflinching and demoralising account of Healey's time as a homeless alcoholic in London during the 1960s. It was written once Healey had got clean and – improbably – become a chess master.

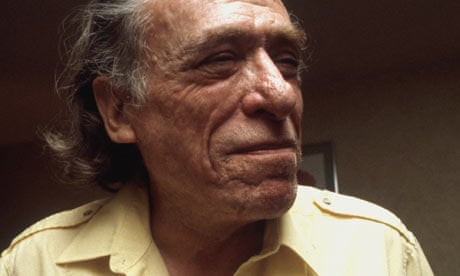

There is, however, one factor that unites the literary homeless throughout the ages: libraries. It is in the library that Super-Tramp's narrator seeks solace from the cold to write himself out of his situation, and it is in the library that Charles Bukowski's occasionally homeless narrator of Factotum finds a secular sanctuary. The past decade has seen some charities establish mobile libraries to cater for the literary appetites of the homeless, yet it is the traditional library that, you suspect, still fulfils a more important role in providing sanctuary, warmth, peace and access to a world of words.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion