It was around 1500BC that sea-faring Greek traders first made landfall on a highly fertile island lying conveniently at the heart of the Mediterranean. In the 3,500 years since, up to and including the recent arrival of up to 400,000 refugees journeying to Europe from north Africa, Sicily’s status as the primary crossroads for both people and ideas in the region has remained intact. Over the centuries its uniquely advantageous geographical position and abundant natural resources have prompted dozens of attempted invasions and seizures of power. Many have been successful, with the upshot often a catalogue of exploitation and neglect as powers great and small took what they could.

However, there have been times of more productive engagement between the island and its changing cast of rulers. A new British Museum show, Sicily: Culture and Conquest, focuses on two remarkable periods: 200 years of Greek civilisation from the 6th century BC and 100 years of Norman rule in the 12th century AD. For these comparatively brief moments in the island’s long history not only did the world go to Sicily, but a flourishing economic, artistic and political culture extended its influence out into the world.

Sicily occupies an important place in classical Greek history. Early grand tour travellers in the 17th and 18th century – the people who reinvigorated exploration of the classical world – often encountered Greek culture in Sicily and southern Italy first, because it was too dangerous to travel to Greece or Turkey, and its temples are widely considered both bigger and better than those in Greece itself. Much of Homer’s Odyssey is set in the western Mediterranean, with the sea monsters Scylla and Charybdis positioned either side of the treacherous strait of Messina that separates Sicily from mainland Italy. The cyclops is also a native of the island. (The story may have its origins in the skeletons of dwarf elephants that were found on the island and are now on display in Syracuse museum. The skulls have a hole where the trunk once was, and would have been found by Greek fishermen with a tradition for storytelling.) Plato also visited Sicily several times from Athens, on one occasion being sold into slavery by a local ruler and only escaping by chance.

The British Museum show, curated by Dirk Booms and Peter Higgs, is packed with treasure never before seen in the UK. It begins with a 7th-century BC depiction on a fired clay pot of a Trinacria, now the official symbol of Sicily, made up of three human legs representing the three points of the island along with Medusa’s head and importantly, three sheaves of wheat. The island’s wealth comes from agriculture and there are numerous fragments of votive offerings made to the goddesses of fertility and the seasons, Demeter and Persephone. One of the oldest pieces in the exhibition shows a more direct veneration of fertility in the form of a 2000 BC limestone door to a tomb apparently featuring male and female genitalia engaged in the sexual act.

From the 8th century BC people from all over the Greek world arrived in vast numbers and began trading grain, oil, wool, salted fish, ceramics, fruit and wine. Wine exported from Agrigento was found in Pompeii and as far away as Switzerland. By the early 5th century BC, Sicily was the envy of the Greek world.

The systems of government on the island varied and even included versions of democracy, but most often communities were controlled by tyrants, authoritarian rulers of a type found all over the Greek world. Although the meaning of the word has now changed, some were decidedly tyrannical, with one forcibly transporting the entire population of a city and another roasting people alive in an oven shaped like a bull. He liked to claim the subsequent screams were the beast bellowing.

But alongside the barbarity there was order and the promotion of culture. Syracuse was an enormous city of 250,000 people, as big as Athens, and was systematically divided into sectors for manufacturing, domestic living, entertainment, religion and so on. Theatre was important, as is clear from the amount of scenes from plays depicted on vases. Sadly, the works themselves have mostly been lost, including Aeschylus’s The Women of Aetna. The tyrants also made lavish displays of their wealth, sponsoring chariots at the games at Delphi and Olympia. Despite there being few precious minerals on the island the rich could afford to import gold and silver, and the skills needed to work it into spectacular jewellery and coinage.

At a civic level they built monumental structures. Hiero II’s 200m long altar in Syracuse was the largest in the Mediterranean, so big that up to 1,000 oxen could be sacrificed on it simultaneously. Tyrants also built the magnificent temples, so many of which survive in some form today. Precisely why they were built remains a matter of debate. As well as a way of honouring the gods they were a display of personal and civic power, and worked as a kind of lighthouse – warning away hostile sea vessels and providing beacons for friends.

The earliest stone colonnaded temple on Sicily is at Ortygia in Syracuse, dedicated to Apollo and built in the 6th-century BC. The builders were so proud of their newfangled columns that they left an inscription saying so. The temple’s survival came from its continued use over the centuries; it was converted to a church, then a mosque then a private residence. Even better preserved are the seven temples at Agrigento, formerly Akragas. Built on a high ridge over a span of 100 years they remain one of the great examples of Greek architecture anywhere in the world. In the 5th cenury Akragas had a population of over 100,000 and its people, according to the philosopher Empedocles, would “party as if they will die tomorrow, and build as if they will live forever”.

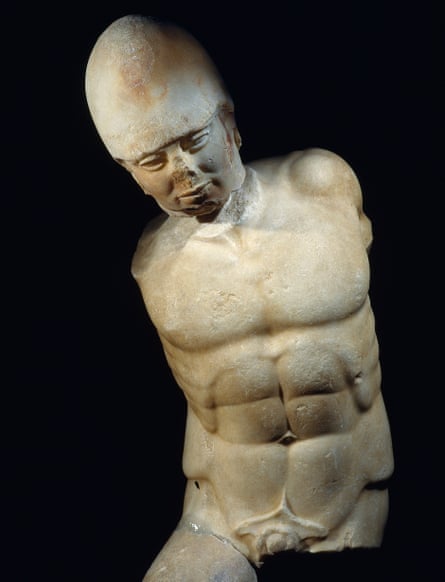

But this was also a site of great violence. One of the star attractions in the British Museum show is a marble statue of a helmeted warrior. Three sections were found, the right thigh, torso and head, and it has recently been restored. Carved in the late 5th century, the figure was probably part of a group and typifies a transitional period in Greek sculpture, where attempts at a greater physical realism – accurate musculature and even veins showing through the skin – is combined with more archaic and traditional forms.

Throughout this period there was much conflict, often between Greeks themselves. Most notably, during the Peloponnesian war, Athenians grew jealous of Syracuse’s wealth and attacked the city. Their fleet was destroyed and many of the survivors died in malarial swamps. Those who did make it to land were put to work in the quarries. However, according to some sources, Syracuse’s ruler Dionysius, a poet, declared that any of the Athenians who could quote Euripides would be allowed to go free. When these lucky few returned home they fell on their knees in thanks whenever they saw Euripedes in the street.

In the end it was outsiders who ended Greek rule. The Carthaginians sacked Akragas in 406 BC. Later Rome turned its attention to the island and sealed control after winning the final battle of the first Punic war in 241 BC. As long as Sicily paid its taxes in grain the Romans cared little about their new province. It wouldn’t be an independent entity for another 1,300 years. After Rome’s fall in the 6th century AD Christian Byzantines and Muslim Arabs competed for domination, controlling the island from Constantinople and north Africa. It was the Arabs that eventually triumphed and enjoyed over two centuries of rule from the 9th century, during which time they brought science and agricultural advancement, introducing new glazing techniques and crops such as sugarcane and citrus fruits.

But tension between the Arabs and Berbers on the island eventually created an opportunity for a new invasion. The Normans had settled in Italy from 1000AD. They were an adaptable and fast-breeding people who were always looking for new territories. In 1061 Roger Bosso and his brother Robert arrived from mainland Italy with only 450 knights. By 1091, via force and diplomacy, Roger had taken control. In 1130 his son was crowned King Roger II of Sicily. He took the inheritance of Greek, Byzantine and Arab cultures and attempted to forge a multicultural society. And for the most part he pulled it off.

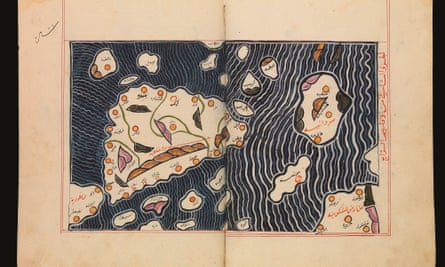

Roger embraced the scientific advances of the Muslim world and commissioned an Arab geographer to make the first new map of the world since the Greeks. He also appointed Arab administrators for his government and encouraged all faiths to come together. The British Museum show includes a book of psalms written in Greek, Latin and Arabic so that converts could follow the liturgy. It was clearly used by an Arab speaker as the text has Arabic annotations. Also in the exhibition are examples of north African carving techniques designed for Norman homes and, uniquely, a quadrilingual inscription for the tomb of the mother of a priest. The inscription is written in Latin, Greek, Arabic, and Judeo Arabic and demonstrates that the priest was following the king’s policies when marking his mother’s death.

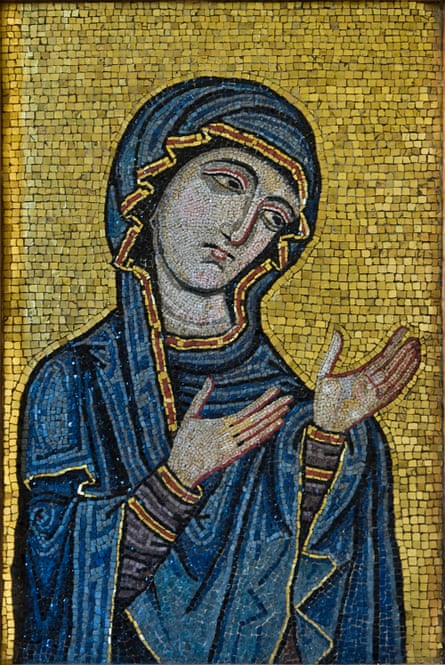

The Palatine Chapel in Palermo is perhaps the best preserved medieval palace in Europe and Roger’s greatest achievement. The architectural influences are Roman, Arabic and Byzantine, with little evidence of northern France. Designs are from the Islamic world in the form of dancers and musicians and there are Latin, Greek and Arabic inscriptions. Roger himself is depicted within the magnificent golden mosaics wearing the kaftan of an Arab ruler. Roger’s careful rule brought all the cultures together in the creation of a court, a culture and a visual language.

There is evidence of this policy in all the great buildings commissioned by Roger and his descendants: a pillar of Palermo cathedral has inscribed on it a verse from the Qur’an – the pillar had been reused from a mosque but plainly no one thought this was a theological problem; and La Zisa, Roger’s grandson William II’s pleasure palace in Palermo was almost identical to ones built by Arab rulers in Baghdad and Damascus for hunting and womanising.

While there is evidence that levels of integration were much greater in terms of the elite at court compared to the ordinary people – Palermo’s districts still carry the names of the religious groupings that lived in them in the middle ages – it was nevertheless an extraordinary experiment in governance that lasted for a century and only unravelled after the death of Roger II’s grandson. Sicily went on to become part of the French, Spanish, and Habsburg empires and essentially just another part of Italy as opposed to a self-determining state run by the most important people in the Mediterranean.

In the centuries since, the island has thrown up its share of great artists. These include the renaissance painter Antonello de Messina, who may not have invented oil painting as is sometimes claimed, but who certainly perfected it; the sculptor Gaggini and the painter Caravaggio who, having fled to the island from Rome accused of murder and pederasty, completed some of his great works there.

There was also a unique flowering of the baroque, with extravagant stucco replacing marble, and later, the Liberty movement – named after the London shop – that was a branch of early 20th-century art nouveau. But from the end of the Norman period Sicily only played a bit-part in the story of the region, and while it remains geographically the centre of the Mediterranean, the island would never again be the cultural centre of the world.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion